Sounds like a good start. Were you able to get any of the motions going, and what motion(s) have you been using otherwise?

Yes I got the bridge anchored FW motion going. Not at full speed yet but it will get there.

Normally I use more of a wrist motion that is much less supinated and has less margin of error for the upstroke escape - it works ok for some things but sometimes gets messed up for some licks.

The bridge anchored FW motion feels like it should give me a more consistent and reliable motion, especially for EJ type licks where string tracking is challenging.

Also @Troy do you think that this motion is amenable to crosspicking, given that the path is slightly curved ?

This is an upstroke escape motion, so it doesn’t do downstroke string changes. That would be a different motion. But if you’re asking can you use a similar arm / hand position and make a motion that can also do downstroke string changes, yes you can. Here’s our lesson on how to do that:

The difference is this arm setus up is a little more pronated, and to do downstroke string changes you use a little more wrist extension. So the whole thing feels a little more like a “motorcycle grip” type pump action of the wrist. But it’s still very similar, so these two “modes” can work together as a family of motions. You play USX lines using the one form, and then switch to this slightly different form and motion if you want to pure alternate.

We’ll eventually do a much shorter, maybe 10-minute chapter on this and add it to section of the Primer. But we wanted to get all this stuff done first since it has all the important foundation stuff like grip, arm position, muting, and so on.

Awesome, that’s exactly what I had in mind. Will check this lesson out, and looking forward to the new vid

Wathing this video - I don’t disagree with your conclusions because it does seem like the amp is doing a lot to help noise control on unplayed, unmuted strings, or at a minimum the bar for arguing it isn’t seems pretty high because there’s nothing muting those bass strings and there’s no real perceprtible rumble. But, your explanation that compression knocks the “big” notes down and takes the small notes down with it isn’t entirely accurate, which makes me think the “distortion heavily compresses guitars” metaphor that we all use isn’t really the full picture.

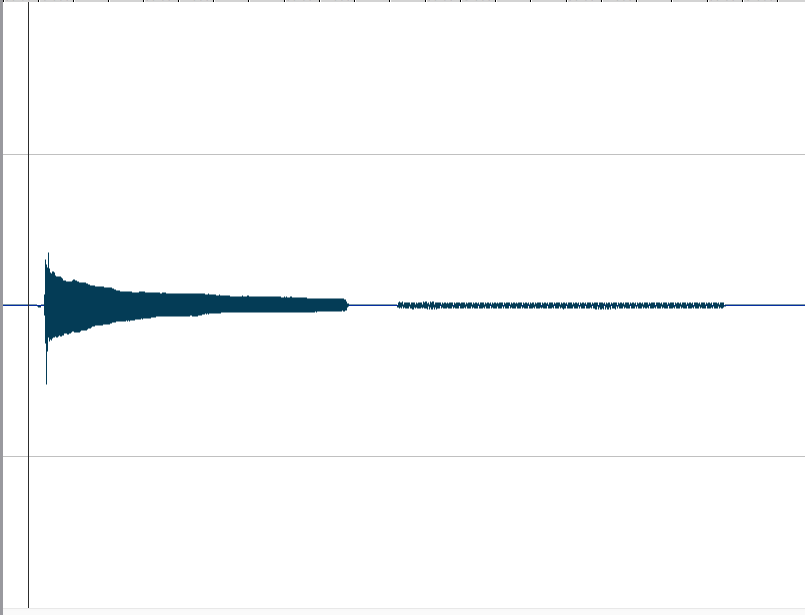

It’s tough to demonstrate this visually, but I tried by recording a DI clip of me playing a single note, then lightly brushing the open E string to simulate the string ringing open, but seperate from the picked note:

You can see the nice big attack of the picked note, followed by a little bit of background resonance style noise after I barely brush the string.

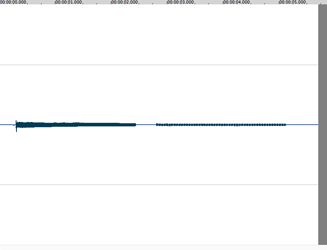

Next, I smashed it with a Sonimus tube compressor plugin:

As you can see. the “big” note has it’s amplitude “compressed” and knocked way down, but the soft note isn’t really impacted and now the differential between the two is pretty small. If you then hit them with some make-up gain they’re both going to ring out a lot closer to the same volume.

So, if a heavily distorted amp was purely just a source of compression here, the resonances would actually get a whole hell of a lot louder. It’s not that a comopressor turns everything down, it doesn’t - in fact, even if the threshold was set to -infinity (so all notes were being compressed), the volume differential between a big note and a little one would actuay shrink as the compression occured, and resonances should become MORE prominent. Yet, they’re not.

I’m posting this mostly because…??? I guess I’m confused why this should happen, yet it clearly is. Technically those resonancesare occuring at the same time as the “big” notes, which could be important. And, I guess, as I’m reasoning through this, this form of a compression is really a biproduct of saturation, as preamp tubes are driven into overdibe by the signal, which would mean bigger amoplitude notes are more heavily effected than really small ones. They may be less compressed but in turn they’re also a lot cleaner, so possibly what’s going on is the “gain” effect and the really snarly, aggressive, saturated sounding picked notes are just stomping all over the background resonances which are by comparison clean and not very saturated? This could have a lot to do with the way distorted notes tend to beat against each other - as an expewriment here I’m picking the E string with authority, and then geeeently picking the G string while the E sustains, and I’m not playing through an insanely saturated amp or anything, but it takes about 4-5 light taps on the string before there’s even a hint of the second note becoming audible, and it’s some time before it really becomes audible, whereas after maybe 10 seconds it becomes pretty prominent and even starts to mask the low E a little.

In fact, just for kicks:

To the best of my ability the picking on the G string (F#, 11th fret, if it matters) is even throughout, and you can here how suddenly it just JUMPS out against the E. It’s like the amp somehow knows to ignore the “noise floor” around big, prominent sounds from the guitar. (EDIT - actually, slight clarification - because this compression is the byproduct of a volume boost pushing the tubes into overdrive, it’s like the boost is less, um, “boosted” on lower amplitude sounds and more effective on boosting larger sounds, I suppose. Someone with some knowledge of amp design could probably shed a lot of light on what I’m trying to say and what I’m hearing).

Anyway, rambling pointless post for the day - check!

I’m pretty sure my explanation is correct here. But always happy to be wrong, and I know you know your way around a compressor. So here is how I think it works.

In its simplest form, a compressor is just a volume knob that only goes down. When you cross the threshold, the compressor cranks the level down. And since a compressor is just a volume knob, any sound happening at that time also goes down with it, which includes both noise and notes. Much like a fader, it has no way of separating the two. This is where I think people in YT comments are getting confused when they’re saying “that’s not how a compressor works, it reduces dynamic range”. Sure, a compressor reduces the dynamic range of the output signal. But it’s not reducing the signal to noise ratio of the sounds that are being input to the compressor. That difference is always whatever it is, as supplied by you and your instrument. So if your picked note is, let’s say, 20db louder than your noise, then it will still be 20db louder than your noise after the compressor kicks in with its level reduction. Hence the reduction in audibility of the background noise right along with it.

As your note dies away, the compressor backs off, and the level of the whole signal comes back up, noise included. This is the reduction of dynamic range that we are familiar with. And it happens faster on the higher strings because those notes don’t have as much overall energy to begin with. Bass notes have much more overall energy, and sustain for much longer, than treble notes. So they’re going to cause the signal to go over the threshold and stay there for longer. Same as running your mix through a bus compressor. Look out for those kick drums. Unless you’re an EDM producer, in which case, pump away!

The intial transient of your pick attack is what really triggers the compressor the most, so the effect works best during continuous playing, i.e. because the transients are repeatedly exceeding the threshhold and causing the compressor to knock the level down. But even the fat note body that happens soon after the big transient is still enough to meat keep the level suppressed for a little bit, until the next picked note comes along. So as long a you’re picking regularly, the effect still works. It’s only if you stop picking and allow the sustain to die that the compressor backs off and the noise comes back up.

So again, the differential in level between intended notes and noise is what matters here. As the noise level approaches the level of the picked notes, the effect is reduced. So in your tests, if you’re not picking the intended notes loud and continuously, while avoiding the low strings as much as possible, there won’t be as much differential in level and you won’t get the silencing effect. Similarly, if you’re picking a note, then letting it die off a little, then brushing the low strings, the compressor has already come up by that point, and you’ll hear the noise. Not much effect there either.

In general playing, if you’re hitting the unplayed strings almost as forcefully as the intentional ones (i.e. wrong notes), you’re going to hear that. Also, if you’re getting lots of fretting liftoff noise on high-energy bass strings, that liftoff noise will contribute almost as much energy to the signal as your intentionally picked but much lower-energy notes on the higher string. So you’re going to hear that liftoff noise. When there is little differential between note energy and noise energy, there is little effect. When picked notes and noise are equally loud, there ain’t no cure for that but better playing.

Please check my math!

I’ll confess - I didn’t even read the comments on YouTube, so first off I apologize for being one more voice in a chorus of people disagreeing with you.

But, technically speaking, they’re not wrong - a compressor DOES reduce the dunamic range. this happens because it’s a very “selective” fader, that only turns down the part of the signal that exceeds the compressor’s threshold.

Let’s say you have a compressor set with a threshold of -20db and a ratio of 2:1. Let’s say that you then hit it with a signal that peaks at -16db, but then quickly decays to a steady state sustain of about -25db.

What the compressor will do, is when it “sees” that peak (if you wanrt to get technical the “attack” control controls how fast it sees the peak, but for now let’s assume this is instantaneous), it will selectively turn down the volume of any part of that signal that exceeds the peak by a factor of 2 - if it exceeds the peak by 2db, it will reduce it so irt exceeds the peak by 1db, if it exceeds by 4db, it’ll reduce it so it exceeds by 2db, if it exceeds by 10db, it’ll reduce it so it exceeds by 5db, and so on.

So, in that hypothetical waveform, the signal peaks at -16db, or 4db above the threshold of -20. A 2:1 ratio will cut that in half, so the peak of -16 becomes a peak of -18, that still decays down to the steady-state sustain of -25db. Your dynamic range has now dropped from 9db (-16 to -25) to 7db (-18 to -25). If you cranked the compressor up to a ratio of 4:1, then your peak that previously went 4db above the threshold would now only go 1db above the threshold, and your dynamic range would fall to 6db, -19 to -25.

Taken to extreme - if you set your ratio to infinity (any signal that exceeded the threshold would be scaled down by an infinite ratio, i.e - reduced TO the threshold), then what you have is a limited, and if - with the same waveform - you reduced the threshold from -20 to -25db, kept the ratio at infinite, and played back that waveform, you’d completely eliminate the attack, and reduce the wave to a flat -25db sustain.

A compressor doesn’t really care what happens below the threshold - the threshold is simply the level at which it begins to act. It’s sort of a selective volume control above that threshold, and it acts by reducing amplitude based on the ratio you tell it to scale sounds down by. The long and short of it is provided your noise floor is below your threshold (and in turn ignored by the compressor) you’re absolutely reducing your signal-to-noise ratio, vy reducing the peak level of the signal while leaving the noise unchanged.

All that said - I don’t disagree with your conclusion, that distortion does seem to do a pretty good job masking noise at the lower end of the noise floor, provided the front end of the amp is being hit by a hot enough signal (if you sustain a note after a long picking run and don’t actively mute the other strings, I bet you other noises will become more present with time). I just think the exact mechanism is probably a little more complex than compression alone, and it seems like a distorted amp just struggles to reproduce two pitches simultaneously of wildly different amplitudes for some reason.

And, for the sake of what we’re talking about here, the mechanism probably isn’t hugely important, since the conclusion matters a lot more than the mechanism. but, from a pure audio engineering standpoint, using a lot of compression on dynamic sources with a relatively high noise floor is kind of risky, since compression reduces amplitude and in turn is often used with a lot of make-up gain, so in effect you’re pulling your noise floor up, sometimes quite a bit.

And, thinking out loud, maybe that’s the difference here - because we’re generating compression as a byproduct of a signal boost, where the loudest parts are getting smashed and pushed into overdrive, whereas in a studio context you’re starting with compression, and then often turning it up afterwards to compensate. Anyway, none of this really matters and Im probably just being needlessly pedantic, so apologies for a long post on a Saturday afternoon!

This is the part I’m not getting. A compressor isn’t a filter. It can’t turn down only part of a signal. An EQ can do that. But a compressor cannot. It can only turn down the entire signal at a moment in time when the threshold is exceeded. Just as an example, let’s say you’re not even using a compressor at all. Instead you look in your guitar track and you find a point where you see a peak in the waveform, like a loud chord. And let’s say you have an average level in mind for this track, like -20 or something. But the chord peaked at -15. So you add some automation points to do a 5dB of fader reduction right during the chord and bring it right back up again after the chord. You’d be doing exactly what a compressor does.

We do this all the time in interviews with lav mics. If there’s a loud moment where a person looks down at their hands and says something, they’re going to be talking right into their mic and it will be super loud. So I’ll go into Final Cut right at that point and add some keyframes to drop their level so they don’t blow out your stereo speakers when you’re watching it. And when I do that, any background noise that’s happening, like the amp hiss or other room noise, also gets reduced.

The reduction in dynamic range is what happens over time. The loud chord isn’t loud any more, so it’s closer in level to what came before it and what comes after it. So the dynamic range of the output signal has been reduced. But at any given instant in time, any level reduction that happens to the signal, happens to the entire signal, noise included. Just as with your fader or the mic in Final Cut.

One thing I will point out that might operate differently is, for example, microphones and their transient response. When you have something like a small diaphragn condenser with a fast transient response, you’ll hear more detail in trebly things like if you record a jingling set of keys. Whereas if you mic that with something like an SM57, you won’t hear as much jingle, because the mic element in the 57 isn’t fast enough to capture the really peaky transients. So for something like a set of keys, a 57 will render those transients as rounded over, and the waveform won’t look as pointy. But the noise floor of the 57 won’t be any different while recording house keys than it will be when you’re recording a less peaky kind of sound like a person singing.

But I don’t think that’s what a compressor is doing. A compressor is just a volume knob. Again, I could be wrong!

I promise you, it’s only turning down the part over the threshold. Think about a limiter - a limiter is a compressor set to turn down peaks indefinitely once they cross the threshold. It if set correctly - doesn’t reduce the perceived loudness (and in fact is usually used to increase loudness, by then boosting the signal after you limit to “make up” the lost gain) at all, just eliminates the peaks. If it was simply turning the signal down until the peak was reduced to the threshold, then you’d hear some audible pumping in the rest of the mix as suddenly, say, that sustained bass note dropped 8db.

Here’s Universal Audio’s explanation:

It opens, right off the bat, explaining a compressor is designed to reduce dynamic range.

UPDATE - though, now as I’m absolutely slamming a mix with a limiter to make sure I’m not dead wrong here, it DOES seem to be ducking the whole thing a little more than my understanding of what was going on would explain. So who knows - maybe I AM wrong here!

This is going to sound very zen, but when you say it only ducks the loud part, what is the “loud part”? It’s like saying, I ate too much today, 2500 calories, but I should have only eaten 2000, so I’m going to eliminate the extra calories. Which ones are the extra ones? Breakfast, lunch or dinner? Some part of breakfast? Some part of lunch? The total amount of calories is what took you over the top, not any particular item.

Similarly, when it comes to the signal, the “loud part” is the entire signal. It’s the total energy of everything happening at that moment in time. The compressor doesn’t know which part you care about and which part you don’t. It’s just an amplifier with an automated knob on it. Here’s how a UA 1176 works:

https://www.masonaudio.org/diy/comp1176

There’s no filter here. It’s just an amp, which goes up or down based on a feedback loop. The amp affects the entire signal.

I’m with Troy, here. Signals are additive. If the waveform exceeds the threshold, the gain reduction affects the entirety of the waveform, including the noise. Compressors (especially accidental ones built into high gain amplifiers) are not smart enough to separate the signal into different sources and then reduce only one of them. As far as the electronics are concerned, there is only one signal, and it gets reduced as a whole.

Edit to add: If your amp could tell which part of the signal was noise and adjust the gain accordingly, it would be easy to turn the gain to zero on the noise only and have noise-free operation at any volume.

@Troy and @induction huh, you guys have me rethinking my understanding of compressors here - Troy’s explanation does a better job explaining the behavior of a distorted amp and I can’t think of any reason why they couldn’t work that way.

For kicks, since this is very much an “if you have a theory, test it” sort of place, I sat down this morning with my acoustic and a condenser mic, and used a couple fans to create an artifical noise floor and recorded a short passage:

Then, I hit it with a pretty aggressive compressor, to try to hear how the noise floor behaved:

…and it DOES seem to duck the hum of the fans a little when the compressor kicks in - this was mixed down using ReaComp to apply maybe 8:1 compression at a threshold low enough relative to the signal to engage really prominently, and a fairly long release to make the pumping more obvious. And, there are definitely points in there where I’m hearing the background noise seem to pump. I’m having some pretty serious doubts here about how I understand compressors to work now!

(Disclaimer - I’m well aware that this compressor is absolutely eating this track alive, but the point here is not to sound good, but to understand it’s behavior a little better!)

Thanks for testing! The fan idea occurred to me as well, but only after the video went up and we started getting questions, and I thought, that would have been a cool citizen-science style addition to the tutorial to clarify. We have a humidifier here that could be brought into service for such a thing.

I can’t really speak to how tubes themselves operate and there may be more going on than just compression in the sense of the way a plugin would do it. But I can promise you that a compressor in its simplest form is just volume knob, and no different than the same thing you would do with a fader.

I’m with everybody! I know this is just a really common turn of phrase, and that you’re being constructive here, as you always are — appreciated. But I will admit, it personally always sounds a little like choosing teams in gym class. Maybe I just have too many scars from Dodge Ball. But I like to think that we’re all collaboratively getting to a more informed place. I will be wrong plenty of times as will others, but overall it’s a group effort get smarter.

Thanks for letting me know about this. I have consistent difficulty with the social aspects of communication, and accidentally insult people on a regular basis. I’ll add this to my list of best practices.

@Drew, I apologize if my post came across as an attempt to pile on or bully you. I mostly just like discussing technical topics. I have built a bunch of compressors, and wanted to share knowledge. On rereading, I don’t think I added anything useful that wasn’t already said. Sorry.

Your post was totally ok! It’s a common phrase and I doubt anyone took it negatively. This is just me taking the opportunity to be reveal how thin-skinned I really am when it comes to internet conversation.

I have occasionally wondered, in an I-don’t-remotely-have-the-knowledge-to-answer-this kind of way, whether a tube amp is a bit like a variable mu compressor

which I thought meant the ratio increases the further a signal is above the threshold but now I’m looking into it and I’m not even sure about that any more

Another great video from the CtC team!

I almost fell off my chair at 3:57 (YouTube vid - several open strings seemingly stop making any noise, despite remaining undamped, when Troy strikes a single note on another string).

Yeah, what Tory said - I definitely didn’t take it that way at all, and in fact having someone else chime in helped me consider that maybe my understanding of the mechanics of a compressor was wrong.

And, honestly, this is how the internet is supposed to work - two people disagree, so we go about trying to empirically figure out who’s correct, and try to form agreement based on the resulting evidence/experimentation/sources consulted, etc. Thesis, antithesis, synthesis, all that. If I’m wrong in something, I’d certainly like to know that!

(Really, my single biggest concern here isn’t that I might be wrong… It’s that, as a guy who’s always favored a lower-gain tone for “shred” playing, if maybe somehow I’m doing myself a disservice not in terms of a more “forgiving” playability, but in making noise control harder than it might be otherwise)

I wouldn’t worry about that. The lower gain sounds are just less noisy, so less noise control is needed. Medium gain blues tones have less audible string noise, and clean tone guitar like an Albert Lee type sound has almost none unless you really whack a wrong string by accident.

What, and miss an opportunity to neurotically worry about something I have no control over?!?