You’re right, it’s really simple, so I’ll try to explain one line of it, and hopefully you’ll see how obvious it is, and how to look at the rest of them.

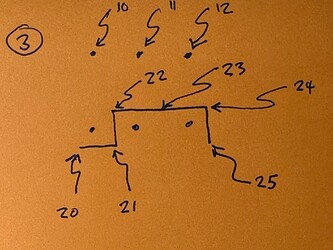

So I put some numbers down to refer to specific points. 10 is one string, 11 is another string, and 12 is the third string. I didn’t give them names because this is any three strings in a row. So, this picture will hold across EADGBE, e.g., it covers EAD, ADG, DGB, GBE, four cases.

So the pick path is represented, in the abstract, by that line. Lets’ consider it starting at 20, then going to 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25.

Big picture:

- It will start at 20, ready to hit 10.

- It will miss 11 and 12.

- It will go back down at the end, so for the NEXT STROKE it will be ready to hit 12.

So pretty much the stroke starts at 20 and ends at 25, as it goes, it hits 10, and nothing else.

The details of the path aren’t mentioned here, e.g., there might be forearm rotation to be able to move the pick from 20 to 21 to 22, and the path would likely be smoother and not so abrupt as I have drawn it, but I was interested in counting how many total strokes there actually are.

So, it starts at 20 hits 10, climbs up above 11 (or possibly swipes it for some people), goes over 12, and then that’s near the end of the stroke, as it needs to stop going in that direction; however, it definitely needs to be going back down, because the next stroke (strictly alternating) will have to hit 12.

Did this make it totally obvious (what it is), or did I add unnecessary confusion?

The main thing that made me draw these is that strictly alternate picking is a severe constraint and it really throws down the law about what is required. I really like its brutal determinism, but some of the strokes can be extremely demanding, and I had never realized that before. What people can try to do is reorganize the strings that they need to hit in order to avoid some of the really difficult strokes.