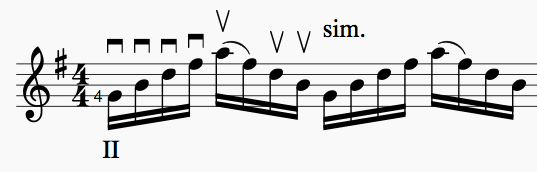

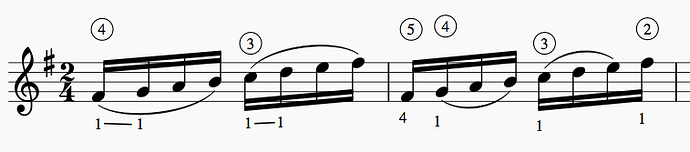

Fair point. I still think it gets trickier to capture some of the physical aspects of playing in standard notation rather than tab; for example:

|------------------|

|------------------|

|---------5/7h9h11-|

|-4/5h7h9----------|

|------------------|

|------------------|

|-----------------|

|---------------7-|

|---------5h7h9---|

|---5h7h9---------|

|-9---------------|

|-----------------|

…are the same notes, or at least SHOULD be if I didn’t screw up the tablature (I’m typing this at lunch without a guitar) but while I suppose you could argue that legato indicators would force you to find some other approach than the bottom to play the indicated pitches, or rather it would be notated differently for that reason, or alternately if needed you could notate the position shifts (though that would get cumbersome)…

That said - this is clearly only applicable to guitar music, so of course if you’re looking at arranging a mandolin or viola or piano part on guitar, or if this is the head of a jazz standard, all of this stuff goes out the window, and how you choose to physically lay a phrase out on the fretboard is as much a matter of personal taste, style, and the vibe you’re trying to convey, more than anything else.

So, I guess I’d say that tab is mostly useful for 1) fairly simple notation for guitarists who don’t read notation, or 2) a deep dive into the playing style of a particular player, where fretting choices are as much a part of the analysis as the actual note choice and phrasing.

Standard notation, though, does strike me as a remarkably elegant system, so while I’m carving out these two specific instances where tab makes sense, I think that in general standard notation is the more useful approach for most musical situations.

EDIT - and, since I’m convincing myself as we’re having this conversation that relying mostly on tab is a handicap, I really do need to spend some time this winter brushing up on reading standard notation.