So as you see from the name of the thread the question is does “go fast and sloppy” apply to all the mechanical aspects like legato, hand sync etc or is it just to do with picking technique? Is there any point in slow practice for developing fast technique?

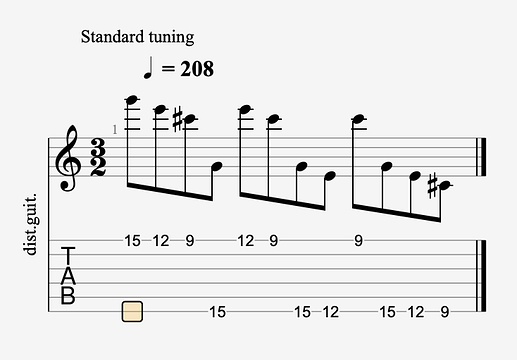

No it does not despite what some on here might say. You can severely injure your hands by trying to go fast with, for example, fretting actions that are complex and involve huge skips across six strings and difficult fingerings like below, which is an example from something I had to record earlier this year:

If you practice this without having an advanced baseline fretting technique there’s a real possibility you could fuck your hands up in a matter of minutes by trying to apply the CTC forum meme advice of “Just go fast, bro!”

There’s a time and place for all practice speeds. You need all of them: slow, medium, and fast.

I think it depends on the problem you are trying to solve, so no

The “go fast” advice usually refers to a sanity check you can do to test whether the picking motion (or legato pattern, or whatever) you are using is capable of your target tempo. Or it can be a device to find new picking motions. In most cases, it requires the lick / riff in question to be already memorised.

But there are probably a million scenarios where the “go fast” thing does not apply

what is this madness?

If there’s any takeaway from this thread I think it should be this. I would not recommend the tasks of memorizing and going fast at the same time. Recipe for disaster.

Just be careful on the forum when you read people saying to go fast all the time. AFAIK Troy and Tommo never really suggested that and somewhere along the line it became a game of telephone and the message got completely warped.

I actually have the video of the very first practice session of me getting that lick to 200BPM 8th notes plus. I will post it as a conclusion to my downpicking thread before the year is up.

It was a passage for a technical metal piece written by a guy who - in spite of my best efforts to convince him otherwise - could not accept that the pattern the way he wanted it to be played was severely unstable, idiotic in its arrangement, and he’d be hard-pressed to find anyone in a live situation who’d be willing to replicate it.

The picking pattern is all downstrokes and is a great example of incorrect technique. The left hand’s pulse is mostly accurately felt as 16th notes, and then he had the bright idea of demanding my right hand pulse be felt as 8th notes. Meaning there’s an inherent de-sync between the hands that has to be overcome.

Suffice is to say while I managed to do it and am proud I did, that passage never got recorded by anyone in any meaningful extreme metal context lol.

No, I don’t think so.

The advice about starting fast is more about seeing if it can actually go fast or are you stringhopping. Or to find a motion that tackles string changes outside of your primary escape etc. You can and should practice slow and medium etc too.

There is a lot of left hand stuff that I wouldn’t apply the same idea of starting fast with.

I think the “start with speed” thing makes a lot of sense when either 1) trying to suss out a mechanical solution that’s efficient at speed for a fairly straightforward mechanical problem (i.e. - alternate picking across strings) or see if a mechanical solution DOES work at speed (i.e - some fretting hand combinations). In both cases, though, the idea is that it’s something you ultimately DO want to be able to do at speed - something like that bizarre example above doesn’t seem like something I’d expect anyone to try to pull off as 16ths at 180-bpm, for example.

Even then, though, I think the limit here is it’s a great way of either solving or proving mechanical solutions, but not necessarily a complete answer unto itself. Metronome practice gets a bad rap here, but if you broaden it a bit to playing against any fixed drum beat, I think the basic concept of taking a mechanic you know CAN go fast, and slowly working up the tempo on a particular lick or drill is still a good way of building accuracy and control, even if it’s an ineffective way of building speed. Or, taking a song you’re working on and slowing it down to 85% of tempo, then working back up to 100%. I think these CAN be helpful, vs just trying to brute force at a speed you can’t quite pull off when it’s not just the mechanical aspect, it’s memorization, coordination, and getting it into the pocket.

But, both are valid solutions, you just have to think about what you’re trying to do, what the particular weakness you’re trying to solve is, and what’s the fastest way to build that ability.

Funny you mention this! That’s similar to what I did when I recorded Petrucci’s Erotomania solo eons ago (3 years!!!). IIRC I did a few repetitions of the solo at 75% or 85% speed (forgot which), then I went straight into recording takes at full speed. I think I did 11 or 12 takes and only 9 and 10 made the cut

Not exactly sure why I did it this way. But in hindsight it was probably a good strategy: 85% or so of the target bpms was slow enough that I could concentrate on some details, fast enough that it was not a completely unrealistic representation of the real thing.

I’m no expert on learning other people’s music, alas, but I’ve found slowing a song down a bit in Reaper with pitch preserved is a good way to focus on not just mechanically getting the notes right, but also sort of getting inside the phrasing a bit and making sure your accents and the groove and whatnot is right, in ways that are way harder to pick out at full speed, save that “something” is wrong.

Yes, in my opinion they’re both required. You have to start with fast (except in cases as given above) to quickly get an idea about what motions are required, but then slow practice lets you understand more what’s going on, and lets your body find out what’s needed.

Here’s some more info on slow practice: Slow Practice — Practicing Guitar documentation

And here’s one way I like to work on some things: Tempo Variations — Practicing Guitar documentation

(I wrote the above so obviously am biased  )

)

Cheers! jz

I think one of the big reasons that other instruments get to avoid the “go fast” approach (as much) is that because they have a set pedagogy, the movements almost all of the people who learn those instruments will be ones that work at multiple speeds. Bowing for the violin, for example - that’s an elbow movement, which we know works for slow speeds and up at the upper limits of high speeds. Ever beginner violin player has using their elbow drilled into them as part of the pedagogy. Tonguing on brass and woodwind instruments are similar.

Plectrum guitar, though, doesn’t have that set pedagogy. We’re each individually making it up on the fly, basically. So we have to “go fast” to make sure that the movements we’re using actually can go that fast, and periodically to make sure we’re not drifting to a different movement mechanic since it can be hard to tell by feeling. Violin, piano, etc, they don’t need to do that, because pedagogically they have had efficient movements drilled into them to the point of automaticity before they even begin to think about going fast so when they do try to go fast, they do so with those efficient motions.

^This! I think that’s where a lot of things get conflated here, and where some misunderstandings happen. People historically like to believe in “cure alls” and are constantly trying to find ways to fast track everything in their daily lives in general, so it’s really easy for many to latch on to a concept like that, condense it, and try to make it applicable to all aspects.

Yeah I second (third???) this. “Play fast” is just a litmus test to make sure you’ve got something that will work. It’s not where we should be ‘living’ in the bulk of our playing/practice.

I think the main point that Troy was getting across is the whole “play it slow and bump it up a few bpm’s at a time” can cause issues, IF you don’t have an efficient technique to begin with. How do you know if your technique is efficient? If you can go fast with it and it doesn’t feel laborious, it’s probably efficient. So find a way to use this same motion at a speed where you are actually in control and are producing good sounds.