Removed my last post because I might learn something from this exchange, don’t want to bow out yet. I have a feeling I am going to get nailed to the cross here, but in the interest of knowledge, I’ll be the one guy who doesn’t buy in all the way. I didn’t pass the bar for nothing.

I know that is not your intention, nor is it my intention to condescend. I’ve been trained to write in a formal, language of argument style. I’ve been told before that it can come across as condescending. My sincerest apologies if that’s how you read my last post.

I think I’m on to something with these ideas, however I not at all supposing that I am above corrections or constructive criticisms. Even in the original EDC thread, there were instances where posters suggested how I might be wrong or situations I had not fully considered. I considered their points carefully in each case and glad of them.

It’s not my intention to bias readers in any direction.

I am genuinely confused about why you feel scale length is anywhere near as critically important as you believe it is in this context. As mentioned, the effects of scale length can be controlled for on any 25.5" scale guitar by tuning down a half step and playing one fret higher.

I am genuinely, positively baffled by the claim that sequences cannot be re-fingered and that there will always be a clear superior choice.

Again, I can control for the effects of scale length by playing one fret higher and tuning down one half step. Moreover, I’m playing exclusively on the scale length the Shawn did not use. I play 25.5" scale guitars.

Shawn played many sequences which are based in 3 notes per string scale shapes and many which involved two way escapes.

No disagreement that they played mostly different lines, though there are certainly common lines between them.

Shawn’s lines were notably faster than Paul’s. I’m trying, to the best of my ability, to understand precisely why this is the case.

I certainly don’t believe that scale length was critical in facilitating Shawn’s speed as I simply have too much evidence to the contrary. There are many recorded instances of him playing 25.5" scale guitars, but he plays the same lines at the same speeds.

Absolutely terrifying playing on an unfamiliar guitar with a 25.5" scale length. Keep in mind, this is a video of him playing a friend’s guitar and starting completely cold.

Shawn didn’t use (1 2 4) exclusively. He used (1 2 4) in conjunction with (1 2 3). Notice the change in his fretting hand here:

I believe much of this in Paul’s case has been him moving away from his early lines, and his newer lines being less suited to the combination of the 3rd and 4th finger, based on my study of Paul’s fretting sequences. Paul still plays his old lines the old way.

I did look into the case of Paul Gilbert’s lines specifically, from different stages of his career. I found that the sequences from the Intense Rock I and II eras are simplified most by using the combination of the 3rd and 4th fingers.

I had a plan for a section of the Chapter I’ve written on fretting cycles which is to be a specific case study on this, but it’s not fully written yet. I’ve been using the working title “The Curious Case of Mr. Gilbert” in my draft documents for that section.

As for the general distinction between 25.5" vs 24.75" being critical, I have a hard time believing that. The difference is the width of the first fret.

Again, not meaning to be condescending here at all, but you haven’t actually provided even the suggestion of a mechanism by which scale length can affect affect these ideas, only the suggestion that it does. I’d be delighted to examine any ideas you’d have on this matter.

If it’s not bloody well obvious to everybody reading my posts, I enjoy analyzing the minutia of guitar technique and I enjoy learning. I would love for you to give me something I can study further. Whether I’m wrong or right, I’d learn something.

So far though, I don’t have that. I have a list of players who play 25.5" scale guitars and who favor (1 3 4) for whole-half patterns. I can name plenty of players who favor (1 2 3) for whole-half who also play 25.5" scale instruments. Govan, Kotzen and Malmsteen just to name a few. Al Di Meola preferred (1 3 4) for half-whole and played 24.75" scale instruments as an example in the other direction.

Right now, I have just as much evidence that scale length doesn’t matter, and what I believe to be an effective control for testing. If anything, I would expect that since (1 2 4) for whole-half is actually more confined, it would actually helped by a slightly longer scale, instead of hampered in some way.

I’m not saying (1 2 4) is superior. I’m claiming it is a less strenuous and more efficient combination which is more amenable to playing at the fastest possible speeds. As I’ve said, I use (1 3 4) in many other contexts. It just doesn’t work for my fastest playing.

Swiping is absolutely a picking hand concern, so we can leave that aside. As for pulling notes sharp or flat, I’d first expect that would be due fretting hand control being underdeveloped for that specific context. That’s not a knock on your technique or experience level either. Until recently, I was hilariously terrible at fingering double-stop licks. I was trying to learn some of Scotty Anderson’s double-stop alternate picking lines and I didn’t have the fretting hand control for it, and I’ve played Holdsworth.

It’s all about context.

The fretting sequences for many lines in Intense Rock I and II are most simplified by using (1 3 4). Were I to play those sequences (or sequences with similar construction), I might still prefer (1 3 4) too.

Again, I was Paul Gilbert fast on Paul Gilbert licks at the age of fifteen. Even with the increase in playing speed I’ve experienced in recent years, I still can’t play those licks any faster, at least not without strain. Paul’s sequences are simply not amenable to being played at Shawn’s speeds.

Shawn is not the only player “fast” player who primarily played 24.75" scale instruments. Many have, with some preferring (1 3 4) and some preferring (1 2 3) or (1 2 4).

Either way, the choice of eliminating the combination of the 3rd and 4th finger is only one aspect of the full picture. It’s not just the combination of fingers used but the specific repeating structures of his fretting sequences which allowed him to play at his fastest speeds.

You’re entitled to believe so and dismiss these ideas if you wish to. I do, however, feel that I’ve presented more than enough to make such a dismissal unfair and unwarranted.

The revelation, the real revelation, is that Shawn’s lines were so fast because they were specifically constructed in such a manner which allowed them to be so fast.

Understanding the principles behind those constructions is what allows us to imitate his lines, or develop our own lines which can be played at those speeds, despite stretches, string skips, or position shifts.

I know that people will be skeptical of me when I contradict the advice of famous players or established teachers, particularly when that advice has been helpful to them. I understand and encourage that skepticism. Truly, I do.

In a case like this however, I’m still genuinely baffled by the idea. There may, perhaps, be a best choice given a particular aim or goal, but the existence of a unique best option seems ludicrous to me.

Taking the simple example of the pentatonic 5s patterns, Shawn Lane and Eric Johnson use different fingerings. Shawn’s allows for greater speed while Eric’s allow greater string damping facility with the fretting hand. Also, note that Eric plays 24.75" scale Gibson guitars all the time, and he played Gibsons almost exclusively in his earlier years (for example in The Electromagnets era, or when he played with Carole King).

Unless you’ve misconstrued his meaning, I don’t hesitate at all in disagreeing with Anton on this matter, amazing as he indeed is.

I’m no authority on the subject, but everything I’ve read suggests that focal dystonia is either psychological or neurological in it’s origins. That seems a reach to me, but that’s an entirely different topic, and honestly it’s one I’m not qualified to speak more on.

Again, if my writing comes off as condescending or confrontational, that is absolutely not my intention.

I like to imagine a debate as a competition against ourselves, our own ignorance and our own biases. The outcomes are that we all win, or we all lose. I want us all to win.

Shawn’s hands really weren’t very large. Very flexible to be sure.

I just had a quick look for some images on Google. It turns out that the top search result for “Shawn Lane hands” is a picture of my right hand that I posted on this forum. I think I may have poisoned my own well here…

I’ve found it helpful to identify different approximate “ranges” on the fretboard. The guitar I play most now has 24 frets and very little restriction to upper fret access, so roughly speaking, I see the “low” frets as 1-8, the “middle” frets as 9-16 and the “high” frets as 17-24. I base my default postures on the middle range and make the necessary modifications as I move up or down.

On my other guitars where the upper fret access is more restricted, I break the fretboard down into low, medium, high and very high, with “very high” beginning where my playing becomes impeded by positions and shapes of the neck heel and cutaways.

I agree with all of this. I play 25.5" scale guitars exclusively, and have a slight preference for the longer scale, but it’s more a consequence of familiarity than anything else. I’ve always wanted a cherry red ES-335 block inlay and the 24.75" scale doesn’t factor against me wanting one at all. The prices on the other hand…

This is largely what the earlier chapters I’ve been planning on fretting postures and fretting techniques are about. With the knowledge that the fretting hand is forever in this flux, I try to identify a collections of idealized postures and discuss the capabilities and limitations of each. With these strengths and weaknesses in mind, we can make judgments based on context and apply them. The skill then is in learning to transition from posture to posture as is appropriate or as is required.

The simple classification of “thumb over” and “thumb behind” is so naive as to be effectively meaningless, and it gives the impression that there is a perfect posture which is fundamentally more correct than others.

I’ve literally been told before that Brett Garsed has poor fretting hand postures and positioning from people who’ve had this notion. Brett. F*cking. Garsed.

The position of the guitar is massively significant also. Two more major variables we can identify the relative distance between elbow of the fretting arm and whether the guitar hangs slung under the picking arm or in front of the body. One of those factors is mostly fixed by strap height and the other is ours of vary at our discretion. Despite what many say, every option offers contextual advantages and disadvantages.

I agree. I do feel we should learn what we can from those models and apply them as appropriate, when and where we can.

Also, we can improve our flexibility over time should we find it lacking. My frontal and lateral finger spans with my fretting hand are about an inch longer than with my picking hand, and my picking hand isn’t particularly inflexible. Growing longer fingers just isn’t an option. You either have large hands that help you in some ways, or you have smaller hands that help you in others.

I wish I had a better term than “most expensive,” so far I haven’t though of one. It ties into the framework of a dynamic economy of movements as opposed to the usual idea of economy of movement. I like that, but I feel it has other connotations that I don’t like as much.

As I’ve said many times now, (3 4) combinations are useful and valuable in many contexts. In some contexts, the are affordable and worth the investment. They’re just not suited to other contexts.

Beef fillet is delicious when aged well and prepared and cooked by an expert. It’s expensive and supply is limited, but the results can be wonderful. Grinding fillet to make hamburger is a very expensive way to make flavorless hamburgers.

Don’t grind fillet to make hamburgers, don’t buy an ounce of gold when you need a pound of lead, and don’t use the (3 4) combination where its not affordable and sustainable.

Thanks for the response, and I understand in part where you’re coming from with the tone. As an attorney I often get the “blunt” and “clinical” accusations. It’ s all good.

I misspoke here and should apologize for that. If we are having this exchange clearly the ideas are valuable. Nothing I’ve said really challenges or seriously questions your ideas, for what it’s worth. Any person reading this would agree as much. I’m trying to get something out into the ether knowing full well it’s going to get some pushback for being too vague and inconclusive.

So, there’s a lot to process here and it’s all very thought-provoking. I did not know you were providing a chapter on Paul Gilbert in the book, what with him being a very strange exception to things. I’ve spent an immense amount of time studying his technique which prompted me to start learning from Anton. Paul has some very curious tendencies that are beyond the scope of this post to detail in full without writing god knows how many words.

I will soon have a metalcast handprint of Paul’s hand from Young Guitar Japan… It’s a rare find. It might come in handy for that chapter if you need a picture reference of my hand alongside it. It’s very common for people to cite “genetics” for Paul’s ability to play 1-3-4. I’m not really sold on that hand size argument, which is why I have defaulted to scale length or physical guitar type as being a potential reason.

There could also be other reasons. Maybe it really is just a function of making his lines easier to play, as you state. This could go back, in part, to what Anton suggests (which might be the case of poor translation from his Russian languge). It’s not so much objective superiority of fretting hand choices so much as it is the most efficient way to play certain lines relative to one’s own physical abilities and instrument setup. That might sound better than what I’ve suggested.

To keep it simple: I don’t know what I don’t know. After reading your post, especially given that clip of Shawn on the Strat, I’m still in the unknown. All I can say is that there is something very strange about Paul’s fretting hand technique. People who subvert his tendency to use 1-3-4 never end up faithfully reproducing his playing. It simply doesn’t “sound” like Paul.

I’m open to the possibility I will never have a concrete answer on this. Maybe the simplest explanation - that it really is personal, subjective choice - is the best answer.

Yes this is very true, except the last part. He has modified much of his playing style. Less shred, more blues. However, he definitely does not play his old lines the old way all of the time. I have a pretty hefty amount of video evidence that you might be interested in that supports this.

I would be extremely interested in reading that Paul chapter as it comes along, even if you just need proofreading which I am trained in as a matter of course for my day job. I think the handprint thing would be cool to add, as well as the borderline absurd amount of video clips I have for various fretting hand choices he has made over the years.

Thanks, Tom.

Very glad.

As you say, it’s all good.

I just want to clarify that your discomfort with these ideas, however vague and ethereal is something I respect. I just can’t really address those concerns to either of our satisfaction until they are more concrete.

I hadn’t announced I was writing it, so I can’t fault you for not knowing. I just wanted to reassure you that I wasn’t ignoring inconvenient outliers. As you say, Paul has some very curious and distinctive tendencies and there’s a lot to be said there. When I have a draft of that particular section, I would be delighted if you’d give it a read through and provide feedback.

That would be very helpful. I think pictures from multiple angles with a 12"/30cm ruler for scale and measurements from a tailors tape might be even better.

Trust me, I’m familiar with this phenomenon.

Bad as it is for Gilbert, it’s worse for Holdsworth and absolutely ridiculous for Lane.

In almost every discussion of Shawn’s playing, the conversation gets derailed by people declaring him to have been an exceptional genetic anomaly. From talking to some of his fanatics, you’d get the impression that he had the intellect of Einstein or Newton with a “supercharged” nervous system. You’d get the impression that he had the compositional skills of Beethoven with the improvisational skills of Coltrane.

It’s all just too convenient to me. It’s an excuse people make to justify themselves not being able to do what he could, and to give themselves a reason not to try. It seems far more rational to me that he was an intelligent, dedicated person who intuitively learned some things that the rest of us haven’t.

I like Shawn’s music and I love his guitar playing, but I won’t deify him. Any progress I’ve made into understanding explicitly what Shawn learned intuitively has been a result of this viewpoint.

With those qualifiers, that’s statement becomes much more difficult to dispute. Context matters.

That video of Shawn playing the Stratocaster is terrifying.

I agree that (1 3 4) is fundamental to Gilbert’s technique. I’ve also noticed that those who imitate his methods closely are better able to replicate his playing. Some might believe that it’s just because those who would do as Paul does in this instance might be more disposed to imitating other aspects of his playing, his tone and his phrasing more closely, which is certainly possible.

I believe that our mechanical approaches create mechanical intuitions which, along with our musical intuitions, informs our playing styles. I think (1 3 4) helps us to share Gilbert’s mechanical intuition and more faithfully imitate and reproduce his phrasing and style.

I couldn’t really replicate Eric Johnson’s playing until I could imitate his mechanics. I get closer to being able to replicate Allan Holdsworth’s phrasing when I deliberately limit my picking technique by adopting his picking mechanics. I couldn’t imitate Shawn Lane’s playing until I adopted his fretting approach. This is at the very heart of the matter.

Please. Specific video evidence of recent Paul Gilbert playing the classic Intense Rock I and II type patterns with different fingerings would be very valuable, especially when direct comparison to older video is possible. I love Paul’s playing but I’ve never studied him to to degree that I’ve studied Eric Johnson, Allan Holdsworth, Brett Garsed or Shawn Lane. I want to do justice to him and his style.

I’ll send you a copy when I’ve a draft written. As mentioned, there’s a lot to write and I want to do the subject justice.

Thank you also.

Hey I just wanted to also add my support to this thread- I think this is a profoundly important discovery. I have always suspected that there was more to this subject than I was aware of and these discussions have been very useful to me. I have always been fascinated by Shawns power licks and solos especially the pentatonic sections and all the groupings of 6 sections. I have made great progress in my playing by abandoning the 1 finger per fret idea that is pushed by lots of educators. This should have been so obvious to me before but now I notice it all the time when analyzing elite players. I will happily buy your book whenever it becomes available! Also- I have really put this concept to work by studying Peter Farrell’s materials. He teaches George Benson’s playing concepts and quotes George Benson as saying that the secret of his playing is NOT in the unusual right hand technique he employs but rather all the magic is in the left hand. Essentially he is using a lot of 2NPS downward pickslanting like EJ or YJM but is also very focused on using 1-2-3 or 1-2-4 and generally avoids 1-3-4 as much as possible as it just never will be as authoritative due to basic human anatomy. Again thanks for all your research on this topic!

Hey Tom Gilroy,

I’m in for a copy. However, I must say that Troy has been so successful because of his expertly crafted video instruction. Picking and fretting techniques are extremely nuanced so seeing these in live action is far superior to reading about them.

For instance, before I enrolled in a month of Masters of Mechanics; I purchased Neoclassical Speed Strategies: The Yng Way by Chris Brooks. In this book, Brooks details DWPS and UWPS and has pictures showing these. However, this was absolutely not close to the thoroughness of Troy’s videos and these picking techniques remained abstract ideas. I simply could not grasp these concepts and put them to use by reading.

I urge and plead that you create accompanied video. This is especially useful for understanding practice exercises. Going through 70+ mp3 files that are 10 seconds long (like in Chris Brook’s book) is extremely annoying and jarring during the learning process.

Chris Brooks did make a whole Yng Way video course, before the book came out. It’s quite good.

I know. I saw the book first, and purchased. I saw that a video was available after the fact. This example funnily enough demonstrates a positive endorsement of video vs book format when the material is the same/similar.

Thank you. Understanding of fretting sequences and fretting mechanics has been important for my own development. I’m glad that some exposure to my ideas has helped you.

I first saw Power Licks and Power Solos in my late teens. I could already pick Gilbert, Johnson and Morse tunes and I had legato in the Satriani or Vai style.

I remember being completely dumbfounded by what I saw, with the exception of some laughter at the most ridiculous examples, particularly because Shawn really seemed to believe that others would be able to play them.

With that said, I’ve come to feel that Power Licks and Power Solos are very valuable documents. Shawn wasn’t quite able to express the how and the why of it all, but he knew the examples he chose were important and the answers were contained within them.

Do as they do, not as they say.

I think that 1 finger per fret has some value in some limited contexts. It certainly seems to make sense initially.

While we have four fretting fingers however, they are not truly independent and they cannot become truly independent. No amount of finger independence work will overcome anatomy.

I wasn’t familiar with Peter Farrell, thank you for bringing him to my attention.

I wouldn’t say all of the magic. George is a goddamn musical Tyrannosaurus.

However, I definitely agree that his left hand technique is mostly overlooked, even by his devotees.

Wow - with a mix of the forensics of picking form here at CtC, a book about fretting hand technique and all the discussion on what effective practice is…there will be a solid go-to source for just about any question related to advancing skills on the technical aspect of guitar playing.

Hey @brutaldeath. Thanks for commenting.

I wasn’t really aiming for the kind of success that Troy has had with CtC and MIM. I wasn’t even planning on selling the book until people told me explicitly that my writing is content they would pay for.

I want to say what I believe is important on these subjects. I want to be thorough, giving my reasoning and showing my work. I want to aim my arguments against the canon of “common knowledge” on the subject and dispel some of the more dogmatic ideas.

Maybe I should be aiming for the project to be successful, and yes, I agree that expertly produced video is one of the for the success of CtC and MIM.

While I agree that fretting movements are subtle, there really is no lack of footage of these movements. The problem is that most really don’t know what to look for.

The fretting hand is forever is a state of flux, moving dynamically between postures. Some postures are relatively stable, others are fleeting. The issue is that we don’t really see what’s happening in action.

Allow me a slight diversion here. One of the core principles in the study of sleight of hand (a hobby of mine) is the idea that larger motions hide smaller motions. Slight variations in how certain movements are “handled” can drastically alter how visible movements of the hand are.

There are reasons why casinos strictly enforce uniform dealing procedures and actions among staff. Even slight variations away from these actions greatly increase the potential for a dishonest dealer to steal from the customers or the casino itself.

Despite all of the cameras and the vigilant, expertly trained security staff, casinos are rarely able to detect these dishonest actions. Instead, they detect instances where there are slight changes in the actions or dealing movements away from the standard actions. This is taken so seriously that even a completely honest dealer will be fired for failing to adhere to standard practice.

You detect sleight of hand by detecting the tells, the variations away from standards that inform you not that something has happened or is happening, just that something can happen. Some tells are very obvious, others are very subtle.

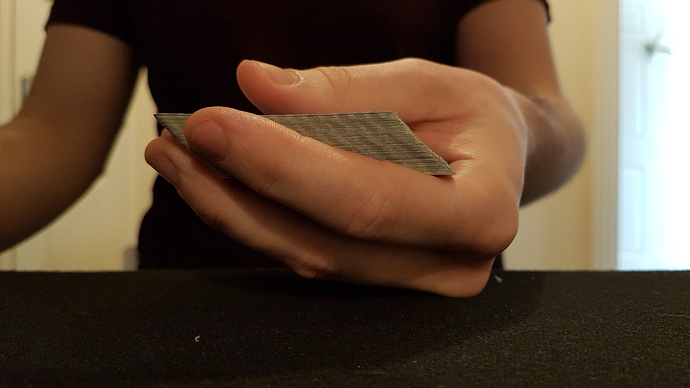

If you let me deal like this, I could rob you.

If you made me hold the deck like this, it’s much more difficult. I’d go so far as to say that I couldn’t do it, though I know of others who could.

If you thought that you’d catch me in the act in the first dealing posture, you’d probably be wrong. You don’t know what I could do or when I could do it. On video, you might notice that something happened.

Here’s a little video of somebody much better than me demonstrating his handling of a move (the bottom deal). A move he’s letting you know he’s going to do.

Believe it or not, from just this video of his method in action, I was able to determine his method (which I will not disclose) and have had success replicating his results. I could do this because I had experience with other methods and handling, and because I have an explicit understanding of the variables involved.

A lot of the study into the fretting hand is like this. It’s intelligent inference informed by understanding the effects of varying parameters and the practical implications of those effects.

My primary aim with the fretting hand chapters is to give you the information you need to be able to make these inferences yourself. I want to equip you to be your own independent problem solver.

I can show you my solutions and I can imitate the solutions of others. I can give you some advice about how to implement those solutions. For the majority, no amount of exercises or examples (video or otherwise) is going to get your fretting hand moving like Allan Holdsworth’s or Shawn Lane’s. You need to understand what they understood. They understood intuitively, and I can’t build your intuition for you. I can help you develop an explicit understanding, which you can internalize and make intuitive.

I understand this, technical instruction through text is difficult for both the writer and the reader. Anybody expecting to understand everything and be able to immediately apply them immediately after a single read through will be disappointed.

I recently had to get a tripod camera mount for work and I have some Kickstarter magnets pre-bought. I might be able to start creating video on these ideas, however there’s a lot to be said anything can be shown.

Also, I simply don’t have the knowledge, skill, time or will to produce video content to the CtC gold standard.

Don’t expect a conventional guitar book with hundreds of examples to be practiced as exercises. Examples will be chosen for primarily for exposition. Pictures will be to provided primarily to communicate principles and, in the sleight of hand language, to show the tells.

I’ve almost never been able to do something by being shown it, I have to have it explained in excruciating detail including why it has to be that way

So, while preparing a section I decided it might be a good topic for a short video. It is not a short video.

Hey Tom, cool stuff. I too will enjoy your book.

Without the enormous amount of naivety involved in asking, would it make any sense to coordinate your effort with @Troy and co? At least the left hand stuff? If you’ve got the material, and they’ve got the technical know-how to produce the amazing video content we’ve all been enjoying, it seems like a natural partnership. I know that brings up the uncomfortable talk about $, because CtC would certainly have to invest time, and you’d be investing yours on concepts you feel (seemingly quite validly) are your own discoveries. But it would surely broadcast the ideas to a larger audience than you (presumably) could on your own, and it’s fresh content for CtC to hopefully get more subscribers. I dunno. I could see it as a mini seminar or something. Just throwing it out there.

Secondly, after watching your video (while I am working, so only partially paying attention) are the more advantageous postures your advocating mainly for electric lead playing? Or are you suggesting the classical traditions should re-think the whole “thumb on the bottom of the neck” thing? If there is a better way, I’d be all for it, tradition aside. Once the right hand tone production is in tact, I think what really makes classical playing so challenging is what it demands of the left hand. The stretches and independence required are terribly difficult and terribly fatiguing, for certain. Your explanation of the weaker pinch grip makes perfect sense for why this would happen…I just can’t see a way, again only in the classical realm, to not use it when playing most of the repertoire and also have the fingers at an angle that isn’t muting strings we’d need for required to bring out all the polyphonic voices.

I would be open to the idea, but I can’t speak for @Troy and the CtC team.

I’ve mentioned I was not really motivated by money when I decided to write the book. I’m aware that saying so is a poor tactic if we were to negotiate something, but it’s the honest truth. My only hesitation is that by agreeing to do so, it changes this from a recreational project that I can complete and release at my discretion, to something I would have to do to a schedule.

I’d be totally fine with the idea of writing the book, and letting the CtC team make from it whatever they would wish to. Maybe announcing the video project, referencing my writing as the source and selling the book through their online store. Troy and the team are cool.

Mainly electric lead and chordal playing, to be true. In most chordal playing on electric guitar, the chords are usually more like “blocks” of harmonic information than the result of intersecting polyphonic voices, or the chords are outlined by a single voice.

However, understanding of the anatomy of the hand and forearms is universal, and the ideas should have merit beyond that particular scope. You’ll notice that most of the greatest steel-string acoustic guitar virtuosos don’t adopt the same playing and fretting postures as classical players for example, their grips are more powerful. I played my share of acoustic fingerstyle so I have some understanding of how these ideas are expressed in that context, but I really don’t have the qualification to speak on how any of it should apply to the classical guitar, or to flamenco guitar either.

Well that’s a shame. As I said, the classical repertoire is difficult stuff. I’d love it if there were a way that didn’t result in a very tired fretting hand. I too have played a fair share of steel string solo acoustic and jazz chord melody. No disrespect to either of those fabulous genres but what’s required in classical, in my experience, was just far more difficult and I can’t see a way that a posture other than what they (classical guitarists) preach as ‘correct’ will work, on the whole. As beautiful as the results of traditional classical can be, it really is almost as if what’s expected in the genre is too much of a demand of the instrument’s design and our anatomy. There was a documentary on John Williams where he mentioned remorse of this aspect of the influence of Segovia. Williams felt maybe more effort should be put into compositions and arrangements of ensemble playing. That would surely lighten the burden of the player, allow for even more complexity of the composition/arrangements, offer more tonal variety. Ensemble works exist, but it’s expected that all serious classical guitarists can play the catalog of Tarrega and Barrios etc. That’s the standard.

Anyway, I digress. Looking forward to your book, however it is released, as these days I’m only playing electric anyway  I’ve really been enjoying not having to file and buff my nails anymore too!

I’ve really been enjoying not having to file and buff my nails anymore too!

Hi @Tom_Gilroy,

Thanks for the thorough and detailed reply.

That’s really great to hear that you have purchased Magnets; these would be awesome to use with your material.

I understand this, technical instruction through text is difficult for both the writer and the reader. Anybody expecting to understand everything and be able to immediately apply them immediately after a single read through will be disappointed.

[/quote]

I’m going to have to disagree with this part of the reply here. I re-read this particular section of the book at least 8 times. That’s simply too much to expect from a reader; especially since video is much more effective. Funnily enough, Chris Brooks realized this and did include two videos with the book, each were under a minute long and lacking detail/clarity.

I look forward to seeing your fretting technique detailed.

Even video clips like this can be super helpful. You may want to write a book just to do it, but you also make a video series building onto this

This video just happened to arrive on the same day I finally gave up on trying to constantly force “thumb in the middle of the back of the neck, fret with the very very tip of the fingers” for legato playing.

I felt a difference straight away and had put it down to the change in wrist angle putting the tendons under less stress but this explanation of different grip types explains the difference in feel/increased relaxation completely.

It’s frustrating that so many people dogmatically assert the dominance of the classical position even while not actually employing it when they play, or at least not all the time.