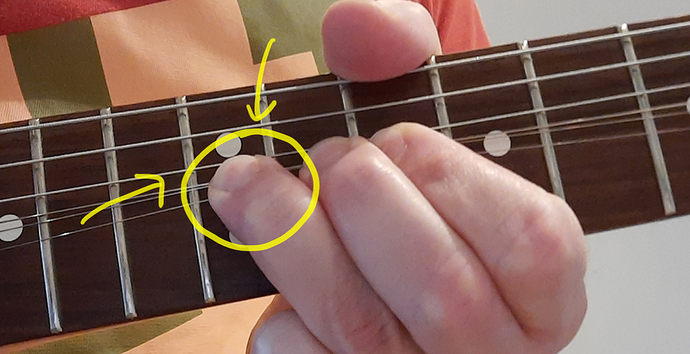

Yep, high-E is hard to bend for me. In most data I’ve seen E and G strings have more or less similar tension (B-string usually has lower tension). which is interesting.

I’ve just tried to do a whole tone bend on both strings, and results are as follows:

- on a G string I have to move it ~0.5 inch

- on a E string I have to move it almost 1 inch.

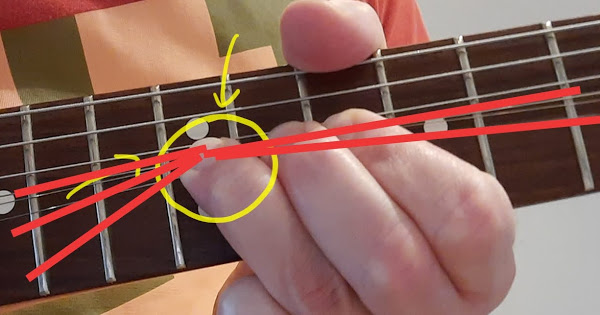

Basically, the angle neccesary to change the pitch depends on many factors, such as tesnion force, Young’s modulus, and cross-section etc. While tension force and Young’s modulus for E and G strings are more or less similar, cross sections are not.

Let’s take a simple formula:

cos phi ≈ (Tk^2 - EA) / (T - EA),

where phi - angle neccesary to make a bend,

T - tension force,

E - Young’s modulus for a string

A - string crosssection

k - koefficient of frequency change (≈1.122 times for a wholetone)

I use 0.009 vs 0.016 strings as reference string diameters. I assumed tension and Young’s modulus for both strings similar (60N and 170GPa respectively).

For this data I get angles ~3.8° and ~2.2°, i.e. E-string requires more angle to achieve the same bending (theoretically). For a 650mm guitar scale-length it gives us:

325tan(3.8) ≈ 21.6mm shift

325tan(2.2) ≈ 12.5mm shift.

(325mm for a 12th fret which is half of scale-length)

Though I used a lot of simplifications the result is in agreement with my experiment and my overall feelings ))