Ok guys, check this guy out. Maybe one of the first electic shredders to go that fast? Do you know of any early shredders who could go that fast (or faster)?

man these guys were the original Nashville cats me thinks.

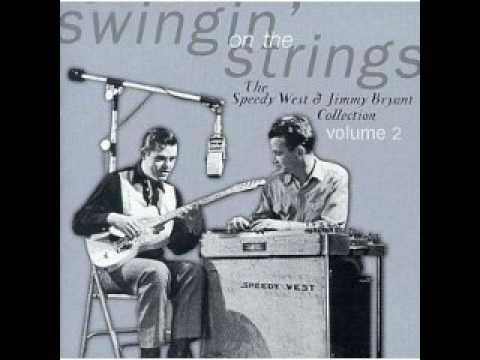

Founds some more info on this guy:

THE JIMMY BRYANT STORY

By Rich Kienzle

IT WAS AN EVENING IN A RUN down part of L.A., not farfrom Pico Boulevard. Skid Row was but a block from Murphy’s Bar, where Speedy West was playing steel guitar. He looked up, as a lean, dark-haired man introduced himself. “Hey, cat,” the man exclaimed in a Georgia accent reeking with confidence, “I like your pickin. I’m playin’down the street at the Fargo Club. When you get off, come down and dig me.” Speedy did, and 35 years later awe remains in his voice as he recalls the first time he heard Jimmy Bryant play guitar: “Ijust couldn’t believe what I heard. He was playing great then.”

When Jimmy Bryant died of lung cancer in 1980, the incredible loss was barely noticed nationally. There were no lengthy obituaries, retrospectives, or deep analyses of his contributions, despite his pervasive influence on both country guitar and instrumental styles.

Bryant was among the first country-jazz guitarists, known for his fluent lines and dizzying technique. His solo records and duets with West were classics. As with the music of Django Reinhardt, Charlie Christian, and Jimi Hendrix, any guitarist can draw inspiration from Bryant. And, like the other guitar pioneers, his recordings still sound years ahead of their time, and probably always will.

Albert Lee, a longtime Bryant fan, says, “I loved his technique, the incredible speed and definition in his playing, and his choice of notes. It was kind of country swing without being too far out. I just liked what he was doing with the guitar; I think it was more exciting than what else was going on at the time. He was getting this great sound out of his Telecaster when a lot of people playing that type of music would have been playing on a hollowbody Gibson.”

Jimmy was bom John Ivy Bryant, Jr., in Moultrie, Georgia, on March 5, 1925 (his longtime nickname was “Ivy”). The oldest of 12 children, he learned fiddle from his dad, a sharecropper. Bryant’s first shoes and overalls came from five dollars in tips he made from fiddling in town. The money also helped feed the family during the Depression, but it was a rough existence. “My grandfather used to lock him in the room or beat him if he didn’t practice the fiddle,” says Jimmy’s son, drummer John Bryant.

It was not much of a childhood, and hating the drudgery of the farm, Jimmy sometimes ran away. When World War II began, he saw his way out and joined the Army in 1943, serving in the infantry in Europe. “He was wounded in Germany,” his son remembers. “A grenade went off and wounded him in the hand and the head. They put him in Special Services.”

Transferred stateside, he convalesced in a Washington, D.C., hospital. Since a country fiddler was not needed in his Special Services unit, he had time to begin listening to j azz guitar seriously. Beginning on a Stella acoustic in the hospital, the 20-year-old progressed quicvdy, iraluenced by guitarist Tany McttDla and by the recordings of Django Reinhardt.

After his discharge when the War ended, he chose to remain in D.C. "He took all his military separation pay and bought himself aguitar and amp, "says John. “After the War he was playing around Washington, D.C., a lot. He was into jazz then, and he was going under the name Buddy Bryant.” He met Gloria, his first wife and John’s mother, at a 'Washington nightclub in 1946. They married in Georgia.

The Bryants stayed there briefly before moving to California. “He drove out to Califomia in a coupe, and then he met (western vocalist] Eddie Dean,” John Bryant explains. “He got Dad started in his band. Then he met people like Russel Hayden, Tex Wilfiams, and Cliffie Stone.”

For the next several years Jimmy eked out a living as an extra in western films while playing the lower-rent country music bars of post-War L. A., including the Fargo Club. After meeting Speedy, the two eventually sat down to play together. “I just knew that it was right, and he did, too,” West says of their first jam session. A local 250-watt radio remote hookup from the Fargo Club proved Bryant’s redemption. West Coast western swing vocalist/ bandleader Tex Williams heard him and phoned the club one night to invite Jimmy to record with him.

On August 9,1950, Jimmy recorded the talking blues "Wild Card "with Williams at Capitol’s Melrose Avenue studio. He played juicy obbligatos behind the vocal, then took a furious, fleet-fingered solo that left no doubt of his confidence with his instrument. It differed greatly from the rougher, Charlie Christian-style playing of ex-Williams lead guitarist Johnny Weis.

Speedy West joined the popular L.A. barn dance show Hometown Jamboree, broadcast over KXLA radio and TV, late in 1949. The creation of veteran bassist/promoter Cliffie Stone and pioneer TV producer Don Fedderson, it became a breeding ground for such West Coast country stars as Merle Travis, Eddie Kirk, Ferlin Husky, Tennessee Ernie Ford, Molly Bee, Billy Strange, and Johnny Horton. Jimmy replaced guitarist/singer Charlie Aldrich in the Jamboree staff band.

“Jimmy was always there for me,” Cliffie Stone reflects. “He was never late on the job, and he was always onstage after intermission and always looked great-good lookin’, handsome guy, clean, dressed, spic and span. He had that nice, clean, boyish look about him at all times.”

The guitarist’s first solo record, “Bryant’s Boogie,” was done at a session with a group of Jamboree artists (Tennessee Ernie Ford, Eddie Kirk, and Cliffie Stone’s band) that produced "Little Juan Pedro."The number itself was an easygoing, medium-tempo boogie-woogie instrumental. He later recalled being nervous, but he acquitted himself exceedingly well. Capitol also changed his name from Buddy to “Jimmy.”

Once Stone heard Jimmy and Speedy together, he featured them as a duo on the Jamboree, dubbed the “Flaming Guitars.” “They built a set, and we sat behind this box, this frame,” Speedy remembers. “It had cut-out flames in front of it in different colors, and it looked like we was sittin’in a pit of fire. And they had one of those smoke machines and a wheel with different colors.”

“Speedy and Jimmy used lots of tricks onstage,” Cliffie continues. “And Bryant had probably the fastest action on the neck of a guitar that I’ve ever heard. I still don’t think anybody’s cut him. He had all the things you look for in a sideman. When he took a chorus, there was nobody who could look at anyone else but him-he was a real showman.”

The duo’s first Capitol session together was Speedy’s first solo date, on April 2, 195 1. They recorded “Railroadin”’ and “Stainless Steel,” West’s first solo single. On June 18, they did their first session as a team. The two Bryant numbers were “T-Bone Rag” and “Liberty Bell Polka.” It was here that Speedy and Jimmy began their special creative process, combining creativity with close listening to each other. The result was a series of dynamic, futuristic recordings that still sound awesome 35 years later.

“If it hit our minds, we’d try it right on the record session,” Speedy explains. "One of us might hum a lick, and the other would start working out the twin guitar harmony to it. If the lick didn’t prove successful, we’d either put it out of our minds, play it backwards, or hum another lick.

"I never did hear one of the songs he wrote, and he never heard one of mine, until we got in the recording studio. We did that on purpose, so we had a spontaneous sound. If we did 10 takes, we never played the same chorus twice after we played something pretty good - like,‘I believe I’ll play that on the next take.’

“And we’d start playing the next take,” West continues, "and sometimes Jimmy would stop and say,'What the hell’s the matter with you? Can’t you think of something else?‘I’d do him the same way. We did this to get an exciting feel. Wejust let our minds run rampant. If we were on a network television show, and a new thought struck us in the middle of the dad-blamed show, we’d let loose and try to do it. It might be a big, badmistake, but it might be something real good, too, so we’d try it.’

Bryant’s solo lines were clearly defined to showcase both his melodic and improvisational gifts, the latter tasteful but still adventurous. One of his jazziest numbers was the medium-tempo “Bryant’s Bounce,” recorded on November 25, 1952. It combines a catchy single-string melody with tasty chord-melody passages.

On "Whistle Stop,"recorded on May 27, 1953, Jimmy plays a syncopated melody line with Speedy adding “whistling” effects with his steel bar. Jimmy later recorded the number with Billy May’s Orchestrafor Capitol. Some of their most stunning moments came when he and Speedy played ensemble, split for their solo breaks, and returned together to end a number.

“Jammin’With Jimmy,” recorded on September4, 1953, is one of the guitarist’s most swinging outings-with a catchy, riffbased melody, some delightful improvisations, and an unexpected, swinging fiddle break overdubbed by Bryant, who played much like his idol and friend, jazz violinist Stuff Smith. Jimmy hummed and grunted as he fiddled, and Speedy teased him about it. Bryant’s answer was typically blunt: “Aw, batshit!” he would snarl (his favorite expletive). “I was gettin’ into it!”

“They fed off of each other because Speedy was really dynamic on those records,” Albert Lee points out. "Jimmy was doing things that I’ve never really heard anybody else do. When I started playing, I used to try to copy solos note-for-note. At that time I wasn’t anywhere close to what he was doing, but I was trying to approximate an attempt at it. He was getting a real malleable sound, not really bending the strings, but getting more music out of it, to my ears. than other players who were playing that kind of music. "(Lee also recalls that one of his biggest thrills was playing onstage with Bryant at the Palomino in L.A. "In 1973 or ‘741 played piano with him one night, " he recounts, "and then a couple of years later James Burton and I played guitars, and Jimmy played fiddle. It was a great feeling, playing with my two biggest influences, and after I took a solo, Jimmy patted me on the back.’)

By late 1953 Capitol decided to feature the duo on an album’s worth of material. Two sessions, one in December ‘53 and one in January ‘54, yielded eight songs for the 10" LP Two Guitars Country Style, released in August of 1954. (For the 12’ version, additional tracks from 1952 were included.) Jimmy contributed a frantic, articulate version of the fiddle tune "Old Joe Clark " that constantly crossed back and forth between country and flat-outjazz–the improvisational passages giving the song unimagined new dimensions. His now-classic’ Arkansas Traveler" was more melodic than jazzy.

On their next session together, September 3, 1954, he used a doubleneck Stratosphere Twin guitar (he owned part of the Stratosphere company), playing on the 12 string neck with its pairs of strings tuned in thirds. It gave him a radically different sound, as though he had overdubbed a harmony part, and the four songs they recorded remain some of his finest moments. The guitar made his solo ballad “Deep Water” so harmonically rich, it resembled Speedy’s steel.

"Flippin’ The Lid "featured Bryant and Speedy on what (with the Stratosphere) sounded like a guitar orchestra, as d id the frantic “Stratosphere Boogie,” one of Bryant’s finest recordings. According to John Bryant, the titles for their instrumentals often came after the fact. “He’d come home and say to my mom, ‘We need 10 tities.’ And they’d just sit there and think things up.”

The Bryant/ West sound was, according to Cliffie Stone, “immediately accepted by many radio stations because they were hot instrumentals, there was no vocal, and a lot of the stations used them for themes, for opening a radio show, before the news, after the news. So it got a lot of exposure. And there was no real team like that.” Speedy agrees: “We got fan mail and performance royalties from all over the world.”

As for the sophistication of their instrumentals, “This was deliberate,” says Stone. “We were more progressive than Nashville. Nashville was the Grand Ole Opry, and that was it.” However, according to Cliffie, Bryant sometimes stretched things. “Onstage, during our shows, I had to sit on the guy to get him to play commercial, and say, ‘Where’s the melody?’ He kept turning up and getting louder. Then Speedy would turn up, then Billy Strange would turn up. The first thing you know, it was killing us.” Talking to Jimmy didn’t always work, for heavy drinking during those years made him short-tempered.

Jimmy and Speedy also began getting substantial session work. They were the nucleus of Capitol’s West Coast country music “house band,” featured on numbers such as Tennessee Ernie Ford’s rollicking 1950 hit “Shotgun Boogie,” sessions with singer Ella Mae Morse, and many more. They did scores of dates with other artists, and for several years were the busiest country sidemen on the West Coast, a point of intense pride for Jimmy.

Continuing conflicts with Cliffie Stone led to Jimmy leaving the Hometown Jamboree in 1955. Roy Lanham replaced him as Speedy’s partner on the show. The final Bryant/West Capitol session came in October '60 and included an unissued 6: 10 version of the old swing standard “China Boy.” Speedy remembers that Capitol producer Ken Nelson gave them a “cut” sign, but Jimmy stubbornly kept playing. In 1960 Capitol released Bryant’s first solo LP, Country Cabin Jazz, made up of his solo singles. Much to Jimmy’s chagrin, Billy Strange was shown in the cover photo, playing an early Gretsch 6120.

Bryant was bitter when Capitol dropped his contract in the late 50s. Speedy recalls that the problem was the same as Cliffie Stone’s: Jimmy’s experimentation simply got the best of him. “Jimmy’s records never did sell as much as mine,” Speedy explains. “He got just a little too far out and over the people’s heads with his melody lines.” His anger that Capitol wouldn’t re-sign him made him refuse to play on Speedy’s early '60s LP Guitar Spectacular. Both Billy Strange and Roy Lanham replaced him.

Yet Jimmy eventually produced records for Capitol (including the Mrs. Miller comedy LPs) and worked on many country and rock dates. His composition “The Only Daddy That’ll Walk the Line” was a #2 hit for Waylon Jennings in July '68 and a Jennings standard from then on.

In the mid '60s Imperial Records country producer Scott Turner, who often used Jimmy on sessions, signed him to a solo contract that yielded six albums from the mid to late '60s, including Bryant’s Back in Town (I 966, with Leon Russell on piano) and Laughing Guitar, Crying Guitar (1966), which combined uptempo numbers with somber ballads. We Are Young, produced in Nashville in ‘66 by Turner, was arranged by guitarist Harold Bradley; it included new versions of two old Bryant/West Capitol numbers-“Whistle Stop” and "Frettin’ Fingers," retitled " Rapid Transit."

The Fastest Guitar In The Country, cut in L.A. and released in '67, was built around numbers such as “Little Rock Getaway”

and “Sugarfoot Rag”

that spotlighted his dazzling speed and technique, which were at their peak. His rhythm section included bassist Red Callender, guitarists Barney Kessel and Al Bruno, drummer Shelly Manne,and saxophonist Jim Horn. "When it was released,"Turner explains, “alot of discjockeys thought that it was sped up. I brought the tracks to Nashville for the DJ convention, and Jimmy sat in the Fender suite that year and actually played the lead parts to the tracks, and that ended that.”

Also in 1967 he teamed with steel guitarist Red Rhodes to cut Wingin’ It With Norvaland Ivy, and his final Imperial effort was the less-than-earthshaking Play Guitar with Jimmy Bryant instructional record.

Patty Murphy, daughter of Murph guitarmaker Pat Murphy, first met Jimmy, a family friend, in the late60s. Jimmy, by now twice divorced, married her in 1970 in Las Vegas, where he was part-owner of an 8track recording studio. "He did some things in there himself, says Patty. “That was the happiest I ever saw Jimmy.”

When his studio partners bought him out, Jimmy returned with Patty to California. Around 1971 or’72 he cut a single on the small Ubande label with ex-Hometown fiddler Harold Hensley, steel legend Noel Boggs, and a rhythm section. The instrumental, “Boodle Dee Beep,” marked the last time these veterans recorded together (Boggs died in 1974). Only Jimmy still played with his old fire.

In 1974 the Bryants moved to Thomasville, Georgia, and in September’75 Jimmy and Speedy reunited in Nashville for an LP produced by steel guitarist Pete Drake. “We went in cold turkey,” says Speedy; “didn’t rehearse or nothin’. Went right to the studio, and I never heard any of his six tunes, and he never heard any of mine.”

Noticing that Jimmy brought his Gibson ES-355 (he no longer used a Telecaster at that point), Speedy spied an unused Telecasterieft in the studio and suggested Jimmy use it to get “the sound we always had.” Originally to be released by CBS, the album never appeared for various reasons, but Speedy says, “We got the same feel we always had, and we hadn’t worked together for 17 years.”

The Bryants moved to Nashville that November, but Jimmy didnl fit into Nashville’s musical establishment, which then mistrusted outsiders. He openly defied their unwritten rules of etiquite. Patty Bryant explains: 'They’d say, ‘You donl go down on Broadway; you don’t go down to all the bars and dives and sit and jam.’ And Jimmy would rather sit and play for nothing than play for money. He would say,‘If I go and work for money, then I have to play what people want to hear. I can’t play what I want to play."’(Asleep At The Wheel’s Ray Benson adds, "Nashville thought if you were a hot player, then you weren’t a commercial player, and they wanted commercial players on sessions. But Jimmy was always a hot player. He was the greatest.)

Bryant performed in bars with his closest Nashville musical associate, steel guitarist Julian Tharpe, another outsider. Having kept up with new musical trends (including rock), he did some custom sessions out of Pete Drake’s Nashville studio. But, since he was not desperate for money, his blunt attitude kept him off the “A” team. “Different people would call him for work,” Patty recounts, “and he’d say’l’m sorry, I don’t work for people like you. I don’t want my name associated with yours.’”

On March 3, 1976, he organized an historicjam session LP in Nashville with nine legendary pedal steel players: Speedy West, Julian Tharpe, Buddy Emmons, Jimmy Day, Hal Rugg, Lloyd Green, Maurice Anderson, Curly Chalker, and Doug Jernigan. With backing from Bryant, bassist Henry Strzlecki, saxophonist John Gore, andjazz drummer Louis Bellson, It’s The First Time consisted of three extended jam sessionstwo Bryant compositions and a 20-minute jam on the old standard “Lonesome Road.”

In the summer of 1977 Jimmy contracted the flu, and it stayed with him when he visited California and worsened into pneumonia back in Nashville. A heavy smoker who spent years in equally smoky clubs, Jimmy entered a Nashville VA hospital late in 1978. Exploratory surgery revealed a malignant tumor in one lung that had spread beyond.

Realizing that time was short, and weakened by chemotherapy treatments, he and Patty returned to his L.A. stomping grounds for several months. On August 27, 1979, his friends organized a benefit concert for him at L.A.‘s Palomino nightclub. Former western bandleader Hank Penny recalls, "I had seen Jimmy just a couple of months prior in Nashville, and he looked great. And when he came into the Palomino that night, I hardly recognized him. He was completely gray-headed, and you could tell he was tremendously sick.’

In April, 1980, he went back to Moultrie. “He wanted to go home to die,” Patty remembers. After a final trip to Nashville that June, he returned home in July. Time was running out. Jimmy entered the hospital, where he died on September 22; he was buried in the Bryant family plot. A guitar, his signature, and the slogan “Jesus’s Guitar Man” (based on the title of a song he’d cowritten) were engraved on his headstone.

With this story, the tributes to his playing, and the possibility of reissues of his and Speedy’s groundbreaking Capitol sides, hopefully a new generation will rediscover the brilliant, inspirational playing of Jimmy Bryant. Cliffie Stone, who first brought him to the attention of the public, sums him up best: 'He was probably the definitive man to have onstage with you, in any condition, under any circumstances in the world. If I had my fantasy band, he’d be the lead guitarist."

Bryant’s 1954 "Stratosphere Boogie’ Of the fifty instrumentals only Jimmy Bryant and Speedy West recorded for Capitol between 1951 and '56, Bryant’s showcase “Stratosphere Boogie” is among the most daring and exciting. It features Jimmy playing at the top of his form, using a Stratosphere Twin doubleneck, utilizing both the 6-string and 12string necks. (Bryant is pictured with this guitar in the March’85 Guitar Player’s Miss Off The Wall article.) Tuning the latter in thirds-its courses tuned EIG, AIC, DIF, etc., low to high-he achieved a “twin guitar” sound, so that what sounds like overdubbed guitars in harmony was actually done live with one guitar tuned in harmony.

Article from:

Guitar Player magazine,

Written by:

Rich Kienzle

(source: http://www.debed.com/lanham/tjbs.htm)

What a territic article. I gotta check out his stuff. I wonder how many other people who were “before my time” were amazing and just a bit under the radar like this. He just wanted to do things his way.

Yeah, I think besides being a shredder, he had some innovations ahead of his time.

How about this - a 12-string (the Stratosphere mentioned in the article above) but the strings tuned in intervals so that he could play harmonized parts.

Sounds like a twin guitar attack to me \m/

Thanks for posting this.

One of the things I like about this community is how it helps me discover interesting guitar music I wouldn’t have stumbled across on my own.

I’m glad you enjoyed it @Frylock - sharing is caring

I like the positive vibe on the forum and the posts from the many knowledgeable guitarists here - so many good reads about our favorite topic

Texas Swing required some pretty major chops! They were listening to the mainstream swingers like Benny Goodman/Charlie Christian–sure hear that here, though the instrumentation and (to some extent) vocabulary’s different.

I’ve known about Speedy West for a while–a Super Monster Killer. Played with Bob Wills–there are a few rare videos of that. But I gather his career was impeded by the fact that there wasn’t a huge market for that kind of virtuoso playing; pedal steel was basically an accompanist gig, and singers didn’t want their sidemen to distract from them.

Which of course was something Les Paul did. That re-tuned 12-string piece of Bryant’s sounds a LOT like a Les Paul exercise in overdubbing and slow-speed tape recording, whereas it’s actually managing to do the same thing with sheer skill and imagination. Amazing stuff. Thanks for digging all this up!

not super easy to find, but there were some early monsters:

Warren Nunes

When I interviewed Albert Lee, he dropped so many names of players that he listened to when he was growing up, and particularly of players who I had never heard of, that we put together a little documentary feature on all of them. It’s called “Heroes of History”:

https://troygrady.com/interviews/albert-lee/analysis-chapter-2-heroes-of-history/

And here’s the YouTube link:

Of course, we’ve got a Jimmy Bryant segment in here. When it comes to the ratio of “skill to available video footage”, Jimmy is strangely underrepresented. As far as I know, there is no footage of him doing his most hard-core playing. The clip we included is the only one we could find.

Clarence White, there isn’t a lot of good footage of him since he died tragically young (hit by a drunk driver while loading gear after a show at age 29 in ‘73). Most famous in rock/country circles for co-inventing the “string bender” while a member of The Byrds. A device that has become a mainstay of country lead guitar for emulating pedal steel guitar sounds. Used by such legends as Eagles’ Bernie Leadon, country session ace Brent Mason, and reigning country shred king Brad Paisley. Clarence had some serious acoustic flatpicking chops and was cited as an influence by Tony Rice. The Kentucky Colonels album Appalachian Swing! is worth tracking down if you want to hear some early bluegrass flatpicking wizardry. As for his electric material The Byrds’ (Untitled) is great as half the album includes live performances of some very different renditions of classic Byrds songs like the Dead-esque 15 minute jam of Eight Miles High.

Hey people! I haven’t been on here in a while, and was searching for the Speedy West & Jimmy Bryant take on this tune, and up popped this post. In case anybody comes across this six years after the fact, I thought you might want to see my transcription which I posted recently on my blog.

https://www.listenfaster.com/main/243/

The two lines jimmy lays down are a blast to play, and a go to warm-up for me.