In terms of overall tonality, I’d be taking the vocal melody into consideration, too. I figure you still end up in Dm for the chorus anyway (I know, I forgot to put the key signature in above).

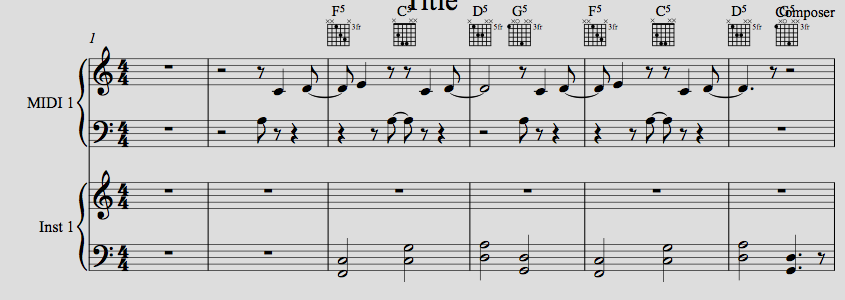

If you wanted to, considering the vocal melody, you could think of the first two chorus chords as Dm/F and Am/C, or maybe Dm7/F and Am7/C. I know it’s more of a “jazzy unplugged” version, but maybe play with the first two chords like this (the higher notes after each chord follow the vocal):

------0--------- —0–0--1–0

—3…--------1 —1–1--1–3

—2…-----2… —0–0--2–2

—X…-----2… —3–2--0–2

—X…-----3… —X–0--0–X

—1…---------- —1----------3

The 2nd section here is me trying to make kind of a “coffeehouse jazz strummer” out of it. I did it FMa9 Ami7 Dmi7 Emi11/G, keeping the first one as an F (I know, it’s “no 3rd,” but…).

I was going to compare “Dani California” to “Last Dance With Mary Jane,” which has kind of the same swingy lilt with Am/G/D, but that one goes to D Major. Check out the chorus, though: Em7 to AMaj, with the vocal melody resting on that C#, quite the contrast to the bluesy verse melody, which sits on the C a bit. It’s definitely an elegant piece of songwriting. He toys with the C note over the Am, doing microtonal bends up on that minor 3 – a pretty typical move but really tasteful, setting you up for the chorus. A Dorian is one way to go over that verse groove (the Petty/Heartbreakers one), if you’re playing around with your modes.

–

I’m of the opinion (I don’t think I’m alone in this) that a root-fifth power chord, especially a distorted one, really functions as just the root note, harmonically speaking. I know the partials don’t start in the harmonic series until you get to the octave, but think of it like certain organ sounds or synth patches – the fifth (or oct + P5) can be a pretty strong partial in a given “note.” A P5 is a funny thing in theory anyway. Playing a 7th chord on the piano, it becomes actually kind of dispensable in the voicing – if you’ve ever toyed with playing tenths on bass (root with an oct+3rd), it’s a great sound without the P5.

Chris Chaney

This can be important on guitar or piano. The idea is, if the bass is covering the root and let’s say the P5 is “optional” at the moment, really you can just hit a 3rd and 7th and define the chord. That frees you up to add color tones instead of doing some blocky root-3rd-5th-7th-color tone 5-note voicing on every chord. So something like an Ami11 could be C, G, D for the guitar, with A on bass. You can mess with it on guitar like this, just pretend the A is the bass player’s note:

----X

----3

----5

----5

----(0)

----X

If you make the jump into chord-melody arrangements, these kinds of “harmonic shorthand” are pretty vital.

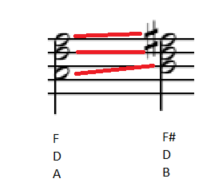

Check out the difference between these two Am7 voicings:

X-----------

X-----------

—5------5

—5------5

—7------(X)

—5------5