I can only share my anecdotal experiences as a player and teacher.

I started playing when I was about 12. I’m 34 now, so this would above been about the year 2001. At first, my father showed me the basic chords and a few riffs he knew, but after a month or two he decided to send me to lessons. I was very fortunate, I had an excellent teacher who is a genuine virtuoso.

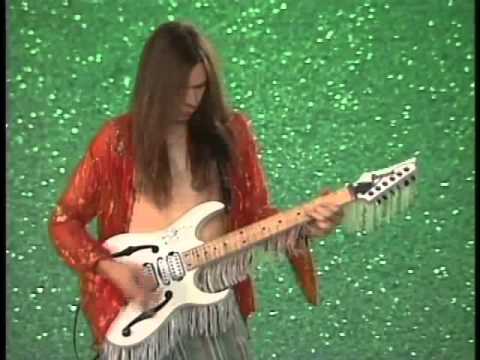

I was mostly playing standard “guitar” songs for the first two years. When I was 14, my teacher introduced me to Eric Johnson’s music. It left a huge impression on me, and this ignited my interest in developing my technical facility. By the age of 16 or 17, I was playing note perfect covers tunes by Eric Johnson, Paul Gilbert and Steve Morse.

My teacher never once told me to practice slowly with a metronome. He did tell me to break down longer phrases into smaller parts, bringing the parts up to speed and then connecting them. However, everything was framed as a problem to solve. I was told to go home and figure out how to play something, not to drill for reps.

I didn’t even know that I was “supposed to” practice slowly with a metronome until my family got broadband internet and I started reading online forums, which was when I was about 16.

The internet convinced me that I needed a practice routine, strarting slowly with a metronome, so I planned out my practice schedule and started practicing slowly with a metronome.

I do have to be honest, I had some issues with my sense of time at this point. I don’t think it’s all that unusual, I had only been playing 4-5 years and guitarists are notorious for these issues. Why do guitar players store a pick between the strings and the first fret? They can’t find a pocket.

I didn’t have abnormally bad time, but it definitely needed work. I could “keep time” if I focused on counting along with a beat, but I had a tendency to rush and if I had to focus my attention elsewhere I would lose my place.

My father (a very good drummer) and my guitar both agreed that this needed to be addressed. Both agreed that the best way to work on this was to play with other musicians. Again, no suggestion of a metronome. In lessons with my teacher, we focused more on playing together. I made efforts to start bands with other musicians my age.

My father is something of a drum shaman, and the real breakthrough came from practicing with him. He kept telling me to “stop counting and feel it.” He told me “if you want to groove, you have to move.” I didn’t really understand what he meant for a few months, and then it came on like a lightswitch. I felt the pulse in my body, I couldn’t lose it. I didn’t have it until I had it. Since that moment, I have never been able to turn it off.

Once I had it, the metronome was just a reference and measurement tool. I would just align my internal clock to the external click. As my father would tell me I would “find it, feel it and forget it.”

The metronome work I had been doing may have contributed, but I really believe that no amount of counting to a click was ever going to flip that switch in me. I had to let go of that entirely. I continued routine practice, starting slowly with a metronome for maybe 12 or 18 months. I hit a major technical plateau and I stopped enjoying the process of learning. I became very goal oriented, and I would be frustrated when I didn’t progress as I felt I should. By the end of it, I was sick of the electric guitar. I was burned out, lost interest in technical progression and I spent the next couple of years playing acoustic fingerstyle guitar, then when I returned to the electric guitar I was focused on phrasing, articulation, note shaping, etc.

It was about 2015 when I started working on technique again, but without any expectation of achievement. I just wanted to explore, experiment and experience the process of learning again. The process which works for me, and which has been working for my students is as follows.

Learning to habituate a low background of tension, thereby increasing sensitivity to tactile and kinaesthetic feedback. Find efficient movement patterns by focusing on what is large, powerful, fast and effortless. Strongly connect these movements to your internal clock. Convince yourself that you can move quickly, for example by using table tapping or a spacebar test (Spacebar speed test | 10 seconds | CPS Check). Build “rudiments”, which are transferrable rhythmic coordinations. Trust your mechanics and your internal clock, let go of any notions of “control” and take a shot at playing at a higher tempo, focusing on your haptic experience. Stop and reset if you ever lose your sense of time, if you get tense or if you lose your haptic “connection” to your movements. Do not stop for accuracy errors; if you can recover from an accuracy error you should, so that you’re training that ability to recover.

Concurrently, build vocabulary based on your rudiments and learn to connect your rudiments. Every new rudiment now becomes a lego brick that you can use to build more vocabulary. If you find something you want to play but can’t, make a rudiment out of it and train it in the same way.

Remember that failure is feedback. Every miss provides information that informs your next attempt. Make failure a goal, and learn to love it for what it can teach you. Remember, there are no negative consequences to failure in practice.

The results are far beyond what I could have ever expected. I’m playing things that are absolutely ridiculous and finding new personal vocabulary daily. The process is working for my students too. Students who have been playing for decades and invested thousands of hours of practice time.

I’ve been reading more about motor learning (inspired by CTC), and I’m currently working through “Motor Learning and Control for Practitioners” by C.A. Coker. The more I read, the more I believe that the traditional approaches to teaching and practicing technique don’t work because they don’t reflect the nature of our learning processes. I’m not an expert in this field, but I reflect on what I learn and consider how it can be applied in my own playing and in my teaching.