Over at bulletproofmusician someone suggested a book by Peter Hadcock, a former asst principal clarinetist for the Boston Symphony and pedagogue, regarding practicing. He’s just got one page on the subject, but what he suggests seems worth knowing (he calls it the Five-and-One Method) - if I could figure it out.

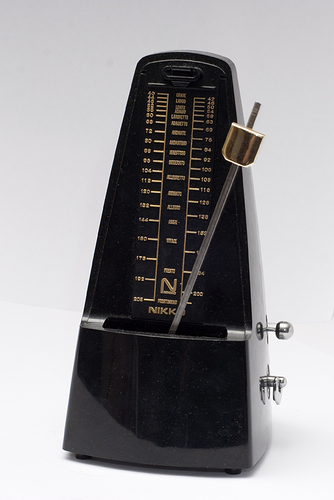

He’s referring to a tough lick in a famous concerto… "This passage is supposed to be played at quarter note = 72, but most of us think of it in eighth notes at about m.m. = 160… Slow down to a tempo at which you know you can play the passage… Assuming your tempo is m.m. 80, here’s what you do.

“1. Play the passage five times at m.m. = 80. 2. Play the passage one time at three clicks faster (m.m. = 92). 3. Play five times at two clicks slower (m.m. = 84). 4. Play once at three clicks faster than you’ve just played it. 5. Play five times at two clicks slower than you’ve just played it.” And so on until 160.

That’s the first stage, there’s a second stage afterwards. But before getting to that second stage - I don’t get the math here. How is a metronome click equivalent to four eighth notes in this scheme…?? What am I missing?

(I’ll fill you in on stage two later, if anyone’s interested…)