The idea for this thread has come from recent efforts to improve my aural skills. I have no affiliation with any company offering ear training programs, and this is not a “sponsored” post. I am simply sharing my own recent experiences.

To clarify, I don’t have “bad” ears, I think it would be fair to say that my ears are average. Over my twenty or so years of playing guitar, I’ve worked out plenty of songs by listening. I’ve practiced recognising intervals and chord types, and I would score quite well if tested.

However, aural skills have never been a strength. My aural skills, particularly pertaining to pitch, has always lagged behind the other elements of my musicianship.

@JakeEstner (who clearly has excellent aural skills) shared this gradation of aural recognition skill previously on this forum.

On this gradation, I would say that I’m typically between grades B & C. I have only very rarely experienced grade A, and I sometimes find myself in grade D when transcribing complex music, or when dealing with a confusing timbre (synth sounds, etc).

I’m sure in part that some of the time, resorting to grade D is the result of my perfectionism, a need to get every detail just right, rather than “good enough.”

The issues are solely related to pitch. I can recognise and internalize rhythms quickly. I have a very good sensitivity to timbral characteristics, for example, on a typical guitar part I would have little difficulty identifying the broad type of guitar and the pickup position, the type of amplifier, etc. Pitch has been the only thing which has given me problems.

Again, I don’t think I have “bad” ears. However, no amount of transcribing or supplementation with interval and chord recognition exercises have helped me to get beyond this stage. Transcribing most songs is pointless busywork, and transcribing complex music can become very difficult and time consuming with little benefit. It makes transcribing feel like a chore, or at best a labour of love.

I’ve always been envious of the musicians I knew who just seemed to be able to hear everything instantly. My old guitar teacher is astonishingly fast at transcribing. One of my close friends who started playing about the same time as me had more aural skill within his first three years of playing than I have now, he just seemed to take to it incomprehensibly fast. I’ve always regarded the people who can transcribe without an instrument, purely by their sense of relative pitch as having a truly extraordinary musical ability. For a long time, I just believed I didn’t “have it,” and that maybe I never would.

I’ve mentioned this in @tommo 's recent thread about the process of becoming an expert, but I’ve I’ve come to believe more and more that when we encounter an expert whose capability and performance seems incomprehensible to us, it’s extremely rare that they are doing what we are doing and simple “doing it better.” Much more often, they are doing something different, which is much more amenable to achieving their seemingly incredible results.

In the last few months, I realised that this was likely one of those cases. So, I began looking for more information on ear training. I really wasn’t sure what I was looking for, but I knew that the approach of practicing interval and chord type recognition (which is by far the most prevalent method in most apps and courses) and just “doing more transcribing” wasn’t it.

I must have alerted the Google and YouTube algorithms, because very soon every advertisement I saw was for some ear training course or app. I looked into reviews for each course, and found that almost all of them follow the same approach of interval and chord type recognition.

Then, I saw an advertisement on YouTube for a course on relative pitch by a website called Use Your Ear. The style of the advertisment was honestly off-putting, it seemed so reminiscent of all of the advertisements for for guitar courses I’m typically inundated with (Guitar Mastery Method, BERNTH, Guitar Speed Builder, Breakthrough Guitar, etc, etc) that I almost immediately skipped it without a second thought.

However, I caught myself, I told myself to at least watch the advertisment and if it turned out to be more of the same, I could forget about it. The advertisement actually said very little, other than that the method of learning intervals and chord types and just doing more transcribing doesn’t really work. So I clicked the link to visit the advertiser. The page gave almost no information away, but it offers a chance to view a presentation on the method. I didn’t like how this all felt, it’s so reminiscent of all of those time-wasting presentation style adverts we’ve all seen before. The page said the presentation is 3 hours long. I really wasn’t expecting much, but I had a large block of free time the next day. So I signed up.

The next day I sat down to watch this 3 hour long presentation. Again, initially this all felt like your typical time-wasting advertisment. A lot of time trying to sell the idea of why relative pitch is important (as if I didn’t know already), some time spend stressing that learning intervals and chord types doesn’t really work without really explaining why, and some video comments from satisfied customers. I was beginning to lose interest and I was ready to close the presentation and move on with my day, and then it became interesting.

There were a few short demonstrations of the problems focusing on interval and chord type recognition. Essentially, recognition of intervals and chord types depends upon musical context and is affected by timbre. In the absence of a tonal framework, we may be able to instantly recognise a melodic/harmonic interval or a chord type. However, when a tonal framework is established, we do not recognise equal intervals as equal. For example, if we establish C major, we do not perceive the major 3rd interval C to E as being “the same” as the major 3rd interval G to B. We may instantly recognise a a maj7 chord in noot position in the absence of the tonal framework, but we do not perceive the Imaj7 chord as having the same quality as the IVmaj7 chord. The tonal context takes priority. If we try to focus on the intervals or the chord qualities, we lose our tonic and our place in the tonal framework. We then need to re-establish our tonic, and we may unintentionally modulate.

Another issue is that our preception of intervals and chord quality in the absence of a tonal framework is affected by changes and differences in timbre. If we play the major third interval in the absence of a tonal framwork and simply make the higher note brighter, we perceive the interval as larger. If the relative brightness or darkness of the individual voices in a chord change in the absence of a tonal framework, we perceive the chord type as having changed.

The presentation went on to explain that the tonal context is fundamental to our perception of music, and that when presented with any melody or chord progression, we naturally attempt to establish a tonality in our mind. Clear examples were provided, and a list of references to peer reviewed studies on musical perception were cited.

The video explains that the internalisation of tonality and the tonal gravity of each scale degree are therefore the foundation of the Use Your Ear method. At this stage, I was positively intrigued.

The video then gave some exercises for the viewer to follow along with, related to identifying scale degree over a tonic drone, retention of a melody in short term memory and identifying a scale degrees, and identifying the chords in a chord progression. You’re told not to use an instrument as an aid. I did really quite poorly.

Then, the presentation included footage of students who have been using this method. After signing up, they were offered 1-on-1 sessions with the course instructor Leonardo, and asked to do excercises similar to those in the last paragraph. The student’s struggles all felt very real. They’re all clearly uncomfortable, and they fail. They feel embarassed and disheartened. They soon resort to their instrument as an aid, and the exercise devolves into a process of “hunt and peck.” This was very much my initial experience when I started trying to train my ears.

The same students were shown after several months of training. Now, they recognise the melodies and chord progressions without using their instruments. Their retention of the melodies and progressions in their short-term memory is more reliable. They still make some mistakes, but they’re much more comfortable and less embarassed. Even their vocal pitch has improved.

This all felt very real. I was more than interested, I was impressed. I was waiting for the video to wrap up and tell me how much this program costs. The price they give is €697. I could not justify that price to myself at the time. Had it been €300 I’d have bought it on the spot. I thought to myself that I could justify €400, but not €700. I told myself I’d keep it in mind for a later time.

Again, I was just about to exit the presentation when they give a discounted price, €397. That’s still expensive, and I can definitely understand somebody saying it’s too expensive. I’ve spent more on CTC overall.

I decided to go for it, and I’m very glad that I did. In the short amount of time I’ve been practicing the exercises in the introductory early units of the course, my aural skills have improved dramatically. My internalisation of the tonic function and the tonal gravity of the scale degrees (the “key’s colours”) has become much more robust.

It turns out, that my internalisation of Do, Mi, Fa and Ti were all very strong, Re being just a little weaker and Sol and La being noticeably weaker. I’m not sure exactly why these weaknesses had persisted through over twenty years of playing guitar (and having taken singing lessons). I imagine that being so consonant with the tonic, I perceived Sol as having a weak pull to the tonic, and that being the tonic of the relative minor, I perceived La as stable or not wanting resolution.

A couple of weeks ago, I decided to install locking tuners and switch from 10s to 9.5s on my Strat (very happy with both changes by the way). I wanted to learn something with a real Stratty character, and I decided to learn Big Log by Robert Plant. That’s a song I like, but not something I’ve listened to all that much. After one listening, I could pretty much play the intro & verse parts immediately. I was a little thrown by some borrowed chords in the bridge section (“Leading me down…”), but I recognised that they were non-diatonic immediately and I could recognise them soon enough. Granted, it’s not that complex a piece of music, but this is the closest to @JakeEstner 's Grade A that I’ve ever experienced.

The realisation relative pitch is not so much the ability to recognise intervals or chord quality, but instead the ability to strongly establish and retain a tonal framework and understand and recognise the notes and chords we encounter by their tonal gravity, function or “key colour” has been incredibly powerful for me.

I’m reminded of when my father (a very good drummer) insisted I spend time with him as a teenager learning to feel a pulse, internalise rhythm, follow a groove and find my pocket. I didn’t “have it” and then one day, in one of our sessions it all came on like a lightswitch.

There was nothing wrong with my ears. There never has been. There were issues with my internal representation of the major scale which affected my ability to retain the tonic and identify scale degrees. There were issues with my approach to and thought processes while listening. We call it ear training, but it is really the mental programming of our internal representations of musical structure. It’s our mental representations and our interpretive processes which improve, not our ears.

I have begun noticing some very strange things occurring. The first thing I noticed was that when practicing melodic dictation exercises, I recognise the scale degree much more immediately than the octave it’s in, which I now only notice afterward. Before, when trying to follow intervals and melodic contour, the change in the height of the pitch would have been the first thing I noticed.

I’ve also noticed that more and more often, I find the pitch I hear (externally or internally) on the guitar without playing any reference notes. It’s not 100%, but it’s definitely rising. Some sort of intuiton seems to be leading me to the correct note on the first attempt. This is very strange, because this isn’t relative pitch and it’s not something that the course promises or attempts to teach.

It’s possible that this is due to the improvement in my relative pitch, with reference to some tones held in memory. Indeed that seemed to me the most plausible explanation. I can’t quite explain it, but it feels wrong.

We’ve probably all seen Rick Beato’s video on why adults can’t develop absolute pitch, and I had read and believed for years prior to that video that absolute pitch was something which could only be learned in early childhood. The working idea being that the development of absolute pitch is related to language aquisition in early childhood, and the closing of that window is somehow vaguely related to synaptic pruning. I had even read the assertion that absolute pitch is not actually learned in early childhood, but that it is present in all infants and it is only retained by a small percentage through their early childhood. We’ve probably all heard that those who have perfect pitch inevitably lose it in later life, with it shifting down approximately a semi-tone.

I have to say I’ve become very doubtful of all of this. Rick Beato is a musican, a songwriter, a producer and a music educator. With all due respect to him, none of these, nor him having two children with absolute pitch makes him an authority on the subject. Further investigation shows that there is some significant dispute in science about what absolute pitch really is, and the idea that it is impossible for any adult to develop it is actually in contention.

People can and do learn to speak new languages as adults, many with impeccable accents. Adults can learn to imitate different accents in their native language. Both of these tasks require the ability to hear and produce phonemes they are unfamiliar with. While the incidence of absolute pitch is higher in people who speak tonal languages, tonal languages do not demand absolute pitches while speaking.

Even the idea that those with absolute pitch “lose it” in later life isn’t really accurate. Instead, people who possess absolute pitch still retain an internal model of absolute pitch, it simply no longer agrees with the external world.

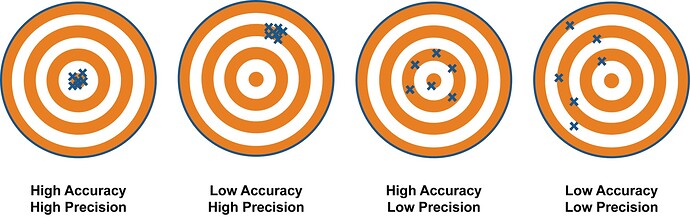

They lose accuracy, but they retain precision.

The only proposed mechanism for this shifting of absolute pitch I’ve found while reading is that it’s somehow related to changes in the cochlea with age. I’ve also read numerous comments by people claiming to have perfect pitch that they have in the past temporarily lost their absolute pitch when they’ve had an ear infection or a particularly bad cold.

We tend to treat the terms “pitch” and “frequency” as being synonymous, but “pitch” is the perceptual analogue of frequency. It’s natural to surmise that absolute pitch is a sensitivity to frequency, characterised by the ability to identify and reproduce frequencies without a reference tone. But this doesn’t really add up quite right for me. The frequencies of notes don’t change as we age, whether we have absolute pitch or not. The frequency of a note doesn’t change when a person with absolute pitch gets an ear infection or a particularly bad cold.

On top of that, frequency really has nothing to do with phonemes in language. We can all distinguish an “ooh” sound from an “ah” sound, the frequency of those sounds not being relevant. How does any of this add up?

What if instead of being a sensitivity to frequency, absolute pitch is a sensitivity to something else entirely? Then, if not frequency, what else?

If we were to record a base tone and produce subsequent tone by digitally pitch shifting the recording of the base tone, the only thing that would be different in an objective, physical sense are the frequencies. Our ears, and specifically our cochleas however, are an imperfect, soft structure.

Could it be the case that as part of how different frequencies of sound interact with the cochlea, there are very subtle different, internal “phonemes” that cannot be measure objectively, but which are subjectively experienced? Nothing so drastic as the difference between an “ooh” and an “ah,” but something of that type, which is repeatable and with each tone having it’s own characteristic phoneme. Could this be the element of pitch perception which enables absolute pitch?

To clarify, I’m not discussing timbre, or an objective interaction of frequencies which could be measured on an external measuring device. I’m specifically referring to the subjective experience caused by the imperfections of the listener’s own ear. Then, they learn to recognise and produce tones without a reference not by the frequency, but by the sensitivity to that internal phoneme.

I spent a few days wondering if this could be the mechanism of absolute pitch, as it reconciles the sensitivity to phonemes in early childhood with the gradual shift in absolute pitch due to aging. I wondered if somebody with perfect pitch might be able to confirm or refute this idea. I even thought about asking here if anybody had absolute pitch. However, it seems that most people with absolute pitch don’t know how it works and can’t explain how to do it.

I came to the conclusion that absolute pitch may indeed be something that could be learned as an adult, but if those who possess it don’t know how they do it and the rest of us aren’t even sure what it really is, it would be unfeasibly difficult to develop as a adult. However, unfeasibly difficult is not impossible. At the very least, my assumptions about what were possible had been examined and their validity had been questioned. Maybe indeed it can only be developed in or retained from early childhood, maybe there is a genetic component, maybe you do need to be one of the “special people.”

Then, I remembered the narrative I’d heard so many times as a teenager about Shawn Lane’s technical facility being due to him being some genetic anomoly. I remembered how I believed I had reached my “genetic potential” for guitar technique in my late teens, and I remembered that when I began to question that assumption, analyse Shawn’s methods and practice them, I was finally able to imitate some of his results. I remembered that my rhythm came on like a lightswitch as a teenager and that my relative pitch is rapidly blossoming now later in life.

Well, I had been thinking about these ideas for a few days, and I came across a commenter who claimed to have developed some degree of absolute pitch as an adult by following a method developed by somebody named David Lucas Burge in the 1980s. I looked into it, and I found the official website that Burge’s courses are sold through, which include citations of two university studies performed in the 1980s examining the effectiveness of his method. That was interesting.

While looking for reviews from those who had taken Burge’s course, I found the course itself hosted online. I usually pay for things, but curiousity got the better of me and I downloaded it and started listening. If the course works I’ll buy it.

The course is quite poorly organised, but interesting. It requires several hours of listening before Burge gives any description of the mechanism of absolute pitch or any exercises to develop it. However, he does eventually explain that a listener has an experience of pitch seperate from the frequency, that each pitch has a subtle sonic character (which he calls “colour”). Again, he explains that this isn’t the timbre of the instrument or anything which can be objectively measured, but a subjective internal experience.

He gives the example of an F# and an Eb. He claims that every F#, regardless of the instrument timbre or the octave, has a subtle “twangy” or “vibrant” quality. He claims that every Eb has a mellower, softer quality. It may have only been the power of suggestion, but in that moment I heard it, and then quickly lost it again when I tried to focus upon it. Then, when I wasn’t trying, I heard it again. It felt absolutely bizarre. He then explains that you can’t try to hear it, you have to relax and let the experience happen.

I really don’t know what to think about that experience. Again, this could easily be the power of suggestion. I’ve studied sleight of hand and magic, I know how unreliable my sujective experience is in that moment. Others might think I heard it because I wanted to, but I don’t feel particularly emotionally invested in absolute pitch, particularly with my relative pitch rapidly improving. Still, I was curious, and so I continued.

The first exercise given is to listen intently to each of the chromatic tones from C3 to C4 and try to associate a feeling or character to each pitch, making a list. Relaxed, effortless listening without expectation. Honestly, this initially felt silly to me, but I got into it, made my list and I wrote down my associations. For example, I felt in the moment that C had a stable, tranquil character and that F seemed to convey individuality, a daring to be oneself. I feel silly thinking about the entire process now.

However, when I picked up a guitar anytime in the last few days, I try to remember how C felt in that moment. Not how it sounded with some known melody as a reference, not the tension in my vocal chords. Only the association. More often than not I’m singing a perfect C.

I genuinely have no explanation for this, but I’m incredibly curious how things progress from here.

I’m aware that this was a monstrous post, but if you have any thoughts you’d like to share on these topics, I’d love to read your input.

). Are you referencing 2 separate courses/methodologies that you’ve test driven? I noted a lot of relative pitch specific items in the first half of your post, near the end I’m seeing more of the absolute pitch phenom mentioned and it sounds like you’ve progressed on both?

). Are you referencing 2 separate courses/methodologies that you’ve test driven? I noted a lot of relative pitch specific items in the first half of your post, near the end I’m seeing more of the absolute pitch phenom mentioned and it sounds like you’ve progressed on both?

Still, I think having to go through the sight singing was an important step for me as it help me further internalize “scale degrees”. I always found it more difficult than melodic dictation, particularly because it needed to be done in “real time” to get all the points on the test

Still, I think having to go through the sight singing was an important step for me as it help me further internalize “scale degrees”. I always found it more difficult than melodic dictation, particularly because it needed to be done in “real time” to get all the points on the test