Fortunately, his last name isn’t Hess.

pretty funny

pretty funny

As far as I’m aware only the middle and ring are connected, the rest are separate. Is there’s any link you can point me to that says they are all connected?

And I think they are only connected in one way, that being the extensor muscles. I’ll have to search again to confirm that, but I’ve looked into this years ago

No, it’s more complex than this. Fingers are not independent in flexion or extension at the anatomical/physiological level, and the zones of the somatosensory cortex in the brain associated to the fingers typically overlap. They’re not “separate” structures at all.

There are anatomical variations, but here’s an overview.

There is a mass action extensor (extensor digitorum communis/EDC) which pulls on all fingers, which is usually the only extensor with a tendon connectiing to the middle finger and often the only extensor with a tendon connecting to the ring finger. Many people do not have an EDC tendon to the little finger.

People simplify things and say that the index and little fingers have “independent” extensors, but that really isn’t accurate all. The extensor to the little finger (extensor digiti minimi/EDM) is absent in many people, and in those where it is present, it exhibits progressive variation. In many cases the EDM tendon is connected to the ring finger, or it may be partially or totally fused to the EDC tendon(s) to the ring and little fingers. Further, the muscle belly of EDM can be partially fused to the muscle belly of EDC.

The extensor to the index finger (extensor indicis/EI) is often described as allowing “independent” extension of the index finger, but again, this is an oversimpliciation. EI typically has lesser dependence on EDC than EDM (if present), but in some cases EI itself has an acessory tendon to the middle or middle and ring fingers also. In rare cases, and additional extensor to the index finger and thumb is present. All of the extensor tendons are connected by junturae (connective tissue between tendons), and the function of all extensors is limited by those juncturae.

The flexor tendons typically don’t have juncturae, but there is no independent flexion at a muscular level either. Flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), which again is a single belly mass action muscle, is the sole flexor of the DIP (small) joints of the fingers. It’s innervation is interesting, the two “halves” of the muscle are innervated by different nerves. This means that it’s possible to achieve some (generally weak) flexion at the radial side, i.e., the index finger without tension at the ring and little fingers, or some weak flexion at the ulnar side, i.e., the little finger without tension at the index and middle. However, flexion at the middle or ring fingers typically requires the activation of the entire muscle belly.

Since FDP tensons insert distal to the PIP (middle) and MCP (big) joints of the fingers, FDP activation results in flexion at these joints also.

Flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) is the primary flexor of the PIP (middle) joints of the fingers. FDS has individual muscle bellies to each finger meaning some degree of individual flexion the PIP (middle) joints is possible. However, there are variations and limititations. In many cases, the FDS belly and tendon to the little finger are absent. In other cases, the bellies for the ring and little fingers are fused.

In any case, FDP flexion is slow. The range of PIP flexion at an individual finger is small and weak when the other bellies are not also flexed.

The primary flexors of the MCP (big) joints of the fingers are the lumbricals. These are intrinsic to the hand, and are much weaker than the extrinsic flexors. While there are individual lumbriucals to each finger, the lumbricals are very unusual muscles. They originate from the tendons of FDP, meaning their function is dependent upon FDP function, which was a mass action muscle. The lumbricals for the index and middle fingers typically originate from single FDP tendons (unipennate), while the lumbricals for the ring and little fingers typically originate from a pair of FDP tendons (bipennate).

Moreoever, the function of the lumbricals is very unusual. In addition to flexion at the MCP (big) joints, the lumbricals also act as extensors of the PIP (middle) joints, depending on the position of the fingers as determined by the other muscle groups. Full extension of the fingers is not possible without lumbrical activation.

Also involved in the movements of the fingers are the interossei muscles. These act primarily as adductors/abductors, but they are important in assisting flexion and extension also.

The exact relationship between the functions of the lumbricals and interossei and the long flexors and extensors is not understood, according to anatomy textbooks I have read.

Finger independence is a myth. It doesn’t exist, because it can’t exist. It can’t be developed or trained. Aside from the anatomical and physiological concerns, the innervations and the mapping of the movements of the digits in the somatosensory cortex are often overlapping, limiting the degree of voluntary control over the muscles involved.

Exercises which aim to develop “finger independence” only train the ability to coordinate the action of these highly dependent structures through cocontraction, to contort the hand into unnatural shapes. Most “finger independence” exercises require fretting postures which are not optimal for actual playing and train coordinations which are not transferrable to actual playing.

At best, practicing these exercises is a waste of time. At worst, it’s developing strain and increasing your risk of injury.

Worse still, purveyors of the idea of “finger independence” often pair it with the usual notions of “economy of motion,” which are overly naive and reductive and which ignore or misrepresent the physical reality of playing guitar. Maybe they insist on “one finger per fret” (which is valid in limited context) and practicing unnatural permutations of the fingers (those endless spider exercises, for example).

In my (relatively short) time teaching, I’ve seen players forcing themselves to play from poor fretting postures with excessive tension in an effort to achieve “finger independence” and “economy of motion.” The more diligent and disciplined the player, the worse the problems can become.

The conventional wisdom and advice regarding the fretting hand is poor at best. It doesn’t work because it’s based upon ideas which are just plain wrong, or which are only valid in specific contexts and are treated as universal.

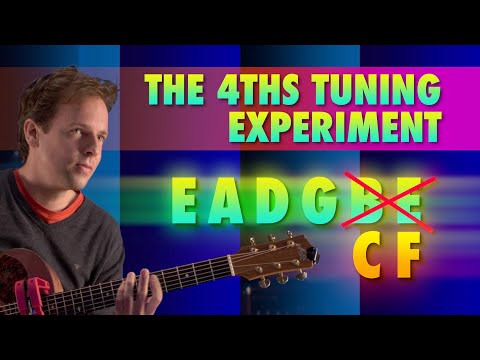

I remember an interview you did with someone who said the reason they don’t keep playing in 4ths tuning is because the minor 3rd adds creativity to their playing.

Right, Wim Den Herder. He claims that for him he’s more creative with the “weird” fretboard layout than the symmetrical one. In actual practice I’m sure the end result is a combination of lots of factors, including how much work someone puts in to building up a large vocabulary. But yes, here’s the clip.

But don’t you think that over complicating the issue? Sure the hand is a single unit with a vast ammount of interactions and connections, but thats a technically, in practice the fingers most definitely have independence or we’d not be able to play guitar or type. As you say it’s form of contortion, and so has tension associated with the other fingers, definitely something to keep in mind. But you can train for increased finger independence and dexterity. The Vulcan hand Salut is an example of that, a lot of people have to train their hand to pull it off.

I can move each of my fingers for all intents and purposes, individually. The only case where thats not true is lifting the ring without lifting the middle. In every other case the fingers move in practice independently. And you can train that coordination in order to preform complex tasks.

I imagine we’ll be arguing semantics here, so don’t want to give the impression I’m disagreeing with you. All that information is good if we can boil it down to common English. And I think we both agree this is why fretting mechanics are so important.

I’m curious if you know anything about the differences in hand construction, some people have so much more freedom in applying force to the fretboard. I posted about this awhile back. Be intrested if you can point me to anything.

What would you suggest for increasing fretting athleticism besides the classic exercises?

I’ve had some substances that made my fingers strong independent and didn’t need no hand.

Do you not think that having a full understanding of your instrument and not having any surprises, is, or at least should be… the goal? That guy is obviously amazing, and you yourself, but I think an instrument is exactly that, a machine to transfer your ideas into reality, just like our voice. I think if you don’t understand your instrument totally, and have happy accidents, then you’re not using it right, it should be just like an amplifier, you playing it, not the other way round, like your mechanics dictating the music.

I do understand the creativity aspect of stumbling across a combination that wasn’t even in your mind and sounds good, but I think thats showing we don’t acually have full control/understanding of our instruments. Thats why I’m really trying to get away from positions and patterns, as it’s not comming from my mind… Perhaps it’s just my own hangup.

One thing I’ve struggled with all my life is spelling, English is a bitch when it comes to that, you can’t just phonetically express yourself, you have to know all the bs spellings that are pronounced different from their actual letter sounds. English is great, but it’s a major issue for people like me with learning disabilities or rather different intuitive perspectives… And thats what the guitar is if you look at it from the wrong perspective, a speed bump. The guitar is one string, the roughly Intune harmonic series, if you understand that, and then layer on the other stings you have a true understanding of the instrument, but most players play without understanding the fundamentals of the instrument they are using. Like me struggling with spelling.

Do you not think that having a full understanding of your instrument and not having any surprises, is, or at least should be… the goal?

I don’t think he is really commenting on that one way or another. I think he assumes any top-level improviser would already be as much as master of their craft as possible.

Instead, I think Wim is saying that even someone who is already a top-level improviser would still find it easier to produce original ideas under the standard tuning than the fourths tuning. And he is suggesting it may be due to neurological factors that can’t be changed, i.e. the way memory works, and the fact that standard tuning is a better design for it.

Doesn’t sound so far-fetched to me, especially given the huge pile of evidence we already have, even from something as seemingly narrow as picking technique. We know that technique exerts a significant subconscious effect on the things people choose to play, and not to play, whether they like it or not. So it’s not hard for me to imagine that other mechanical aspects of instruments and tuning have similar effects.

even from something as seemingly narrow as picking technique. We know that technique exerts a significant subconscious effect on the things people choose to play, and not to play, whether they like it or not.

Thats a big reason I posted this topic, as in my own experience, my satisfaction as i’ve been learning to play comes from, lets call it wanking, to be vulgar and direct, just shredding fast. It’s a dick measuring contest. I can do that now after years of practice and anxiety, but now I’m faced with the musical issue, the communication issue, I can go radadadadada non stop, but thats just some guy in the corner jerking off, and hopefully those kinda people get arrested and told no! lol. The musically takes genuine mental effort, not learning licks, not learning phases, but learning the language of music. And learning to an intimate level the instrument. And then they can acually express themselves in a manner thats meaningful to other people, just like we are doing now, we have a relatively intimate understanding of English, and can juggle back n forth without much issue. We acually don’t want random influences to interfere with our juggling. We want consistency.

I think Wim is saying that even someone who is already a top-level improviser would still find it easier to produce original ideas under the standard tuning than the fourths tuning.

But what about different languages? The tuning of guitar is essentially a different way of expressing yourself, like a different language. The notes are all the same, they don’t change, but the placement of or arrangement does. But the inner voice/soul/intention stays the same.

How can a different language stifle your inner expression unless you’ve not got a full command of that language? Like for me to post here I have to check over and over my spelling, it’s a major pain, it is a speed bump. Though because I love music and guitar I’m posting here when I should really be doing my uni work which I’ve got to present in a raw fashion to my tutor with out much preparation in a few hours, but I’m ok with that, because raw expression and vulnerability of my knowledge is acually how I’d rather express myself, over a pre planned chest puffed out attempt at impressing someone kind of thing. We can all plan for the future, but how you react right here right now is all that truly matters.

I’ve read that the guitar has evolved the way it has, (standard tuning) so guitarists could play over themselves, so strike a chord, pose… lol vogue…

And then solo over that chord. It’s a true solo instrument if you use it right, you can do backing chords and solo using standard tuning. Same as piano. G

Though unlike piano if you start with guitar you’re going to face music theory as a brick wall. Due to the constant repeated octaves in the same position and anywhere else you go, it’s a mess unless, you understand the basics of music, which is the overtone series. Thats the starting point most of us have jumped over in order to puff up our chest and shred.

He claims that for him he’s more creative with the “weird” fretboard layout than the symmetrical one.

Wow, he is a wonderful musician! I believe that what he says is true—that he feels constrained by 4ths—but I don’t think it’s from the regularity, perhaps it’s from the serious constraints that 4ths impose.

For example, I can’t play a grand barre chord on my six-string guitar, as it is tuned in 4ths! You can see the problem: The lowest string is Eb, so the highest string is an E, so my index finger can’t barre! I’m basically OK with limited chords as I play electric and too many strings at once sound mushy, hence I stop at around four notes in a chord or so. There is a lot of regular music that I just can’t play as a consequence.

This is a very enjoyable interview where Tom Quayle and Ant Law talk about the pros and cons of 4ths (jump in around 12:00 if you’re in a hurry). In summary, they suggest that if you tune in 4ths, STAY AWAY FROM FOLK MUSIC AND ITS DERIVATIVES, and it’s true (or you’ll be sad).

And note that at the end they talk about Alan Holdsworth, where they were very excited about how he said that if he were to start again, he’d use 4ths:

Allan is literally saying that the b string is a speed bump. A hang up in expression and jazz.

He is literally saying that the inner voice is more important than any guitar tuning or picking, and what has been the entire point of this topic.

You can’t go fast if you don’t know where you’re going.

And that doesn’t even mean pure shread speed, it means the speed between your inner voice and the instrements physical expression. Using it as a tool, an amplifier of your inner voice.

The main point for posting this is I’ve been frustrated for years dealing with music theory and the guitar, and I think this is a massive issue thats ignored, if you come to music theory and guitar at the same time you are going to hit a brick wall, the number of strings and octaves is overloading, and it blinds you to how simple music is as a language. Thats why Allan is saying he’d tune in fourths, as it makes the guitar more logical, and you don’t have to think as much to express yourself.

The guitar is an instrument right? Not a cd player.

The guitar is an instrument right? Not a cd player.

I don’t understand your meaning here.

As for fourths tuning - you limit yourself using it…or not using it.

I see no ‘brick wall’. I see a steeper learning curve. One that’s inherent with the instrument. Like the difference between learning clarinet vs oboe.

The dual reed instruments are harder to learn at first. Once your embouchure is developed, it’s not such a big deal. The oboe’s fingerings are the same as for the upper-register of a clarinet.

If you understand how the fretboard is laid out, which isn’t that hard to grasp, the octaves and number of strings becomes much simpler. I’ve never felt I hit a brick wall of any sort.

But don’t you think that over complicating the issue?

No, I think anything else is an oversimplification. If we want to describe how the fretting mechanics of great players actually function, or we want to be able to prescribe training methodologies that actually help to bring students to that level, then we need to understand the constraints of the system we’re working within.

I don’t need students to know the anatomy/physiology/neurology and the technical terminology. I do need students to understand what skills they’re developing and the contexts they’re developing those skills in.

the hand is a single unit with a vast ammount of interactions and connections, but thats a technically, in practice the fingers most definitely have independence or we’d not be able to play guitar or type.

No, they don’t. Fingers are not independent.

Fingers have some capability for individual movement, which is limited by the position and movements of the other fingers. The degree of limitations are dynamic and contextual.

This isn’t a technicality, and this isn’t me being pedantic. Words mean things, and what fingers have doesn’t constitute “independence” by any of its definitions.

It must absolutely be stressed that terminology matters. It forms unconscious biases in students about how things are “supposed to be.”

But you can train for increased finger independence and dexterity.

You can absolutely train dexterity and fine motor control. You cannot train or develop finger independence, it doesn’t exist and cannot exist.

You can only train to operate better within the confines of your finger interdependence. In order for that training to be transferrable to real guitar playing, the skills and coordinations you’re training must actually be transferrable to real guitar playing.

The distinction matters. You can become highly adept within the constraints of finger interdependence. You cannot eliminate that interdependence, it will always be present.

It informs what is comfortable and intuitive with our dexterity. When applied to the instrument, it informs what is naturally idiomatic to the instrument. As we approach the limits of what is possible on the instrument, we feel the effects of those constraints. Some who feel these constraints are an obstruction to their progress will try to push through, fighting their own anatomy and physiology. You can’t fight yourself and win. Instead, we must be sensitive and adaptable, and learn to flow around the obstacles. In many cases, we can actually exploit those constraints, and make them work for us rather than against us.

The Vulcan hand Salut is an example of that, a lot of people have to train their hand to pull it off.

The Vulcan hand salute, and other hand contortions are not evidence of “finger independence,” only that it’s possible to learn to coordinate the (highly dependent) opposing muscle groups to create such contortions (and again, within definite anatomical/physiological limits).

I can move each of my fingers for all intents and purposes, individually.

Individual movement within constraints determined by the position and movement of the other fingers is not independence.

And you can train that coordination in order to preform complex tasks.

You can absolutely train coordinations to perform complex tasks within the anatomical/physiological constraints. The question is how to best achieve the desired results within those constraints, either by best facilitating complex coordination (difficult chording, for example) or by abandoning complex coordination entirely, instead exploiting simple coordinations which are naturally informed by those constraints and which are more amenable to performing the given task.

What would you suggest for increasing fretting athleticism besides the classic exercises?

I can write more later, and I promise that this isn’t a deflection, an attempt to advertise or change the topic.

The first step is that you’re going to have to acknowledge that the dogmas of “conventional wisdom” in guitar technique have coloured your presuppositions about how things are. Then, be open to the possibility that the very foundations of that “knowledge” are deeply flawed. Understand that like anything you believe, it forms a part of your self-identity. You’ve worked hard to learn what you “know,” and you’re almost certainly going to resist letting go of it.

Reflect on your question and ask yourself what assumptions you’ve made in asking it. It’s not what you don’t know that gets you in trouble, it’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

Students come to me with decades worth frustration, anxiety and habitual tension. These are good players, often professional or semi-professional musicians. Some of them are guitar teachers themselves. They’ve listened to all the “conventional wisdom” and diligently worked on all of the “classic” exercises, being sure to practice “correctly.”

All I really do is show them a different path. I teach people how to develop the sensitivity to recognise what “right” feels like. You can’t “try” to do this, you can only be open and receptive to the experience. I can’t make the lightning strike, I can only help you to create the conditions for the storm.

I can explain mechanics and give cues on form. I can point to specific “rudiments,” or transferrable coordinations which you can develop and which will form the atomic units of your mechanical vocabulary. I can teach you how to develop and train your own rudiments. None of that will achieve anything unless you’re sensitive and open to the experience.

I’ve only been teaching guitar about a year now, and I’ve witnessed some drastic transformations in that time. Every one of them has had to let go of some presupposed ideas of how things are “supposed to be.”

My sample sizes are still relatively small, but the success rate is already highly significant (statistically speaking). Far beyond anything I could have reasonably expected. There are no guarantees and I certainly don’t claim to know everything, but the evidence so far is that what I teach works.

You don’t even have to take my word for it, right from this very thread:

I agree with Tom 100%.

Not because I’ve taken lessons from him - but because his lessons work.

All I know is that by listening to Tom, I made more progress in two months with my left (and right) hands than I had in the previous two years the ‘normal’ way…and that is not an exaggeration.

Other students of mine have posted similarly positive testimony in other discussions.

Whether you realise it or not, you’ve revealed a lot of your presupposed notions of how things are “supposed to be” and your subconsious biases to how things “should be” here in this thread. You need to confront that.

I imagine we’ll be arguing semantics here, so don’t want to give the impression I’m disagreeing with you. All that information is good if we can boil it down to common English. And I think we both agree this is why fretting mechanics are so important.

If it seems like I’m arguing semantics, that’s not at all my intention. I’m trying to use language that communicates ideas without implying something or encouraing inferences contrary to my intended meaning. Terminology matters and words mean things.

I’m curious if you know anything about the differences in hand construction, some people have so much more freedom in applying force to the fretboard. I posted about this awhile back. Be intrested if you can point me to anything.

Here’s an introduction to the hand:

https://humananatomy.host.dartmouth.edu/BHA/public_html/part_2/chapter_11.html

The “simplfied” anatomy of each muscle/tendon/etc well covered and freely available on sites like KenHub and Physio-Pedia, though they don’t typically explain all the variations (or “types”) across populations. To my knowledge, there’s no comprehensive overview of all possible variations of hands across populations online. If you search for articles with the name of any particular anatomical structure and include “population variations” in your search, you’ll find information on the variations which occur, though it can be difficult to read.

There is a book written on this subject written for classical guitarists, which I became aware of recently. The overview of the anatomy and physiology is quite good, but the specific technical instruction (focused mostly on the plucking hand) is solely in the context of classical guitar (on which I’m not qualified to comment) and does not readily translate to the context of electric or steel-string acoustic guitars.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/078669047X?psc=1&ref=ppx_yo2ov_dt_b_product_details

Allan is literally saying that the b string is a speed bump. A hang up in expression and jazz.

He is literally saying that the inner voice is more important than any guitar tuning or picking, and what has been the entire point of this topic.

Interestingly, while Allan has expressed that viewpoint, there were things in his mechanical vocabularly that were specifically facilitated by the G to B tuning. For more information, this video by John Vullo is an incredible work

Timmothy Pedone from Sharp Eleven Music also released this very insightful book

He is literally saying that the inner voice is more important than any guitar tuning or picking, and what has been the entire point of this topic.

Well, there are two questions: (1) what does one want to play, and (2) does one have the chops to play it?

Both questions need a good answer, but (1) comes first, as it dictates (2).

Forgive me for not being able type out a long response that your efforts deserve, I struggle with that. But I have a few things.

No, they don’t. Fingers are not independent.

But this is like saying we all are not independent individuals. Because we’re massively influenced by our environment and our connections in life. But in practice, we face the world as an individual, just like the fingers move independently. You can lock the other fingers solid, and be able to move a single finger by itself. Yes it’s limited, but from your argument the only time a finger will act independently is when it’s chopped off. And the fingers literally have their own muscle associated with them. They maybe intertwined with the rest of the fingers and body and mind, but they can move separately. With very little involvement from the others. I can move my index finger with next to no movement from the rest, for all intent and purpose, that finger is moving independently. Django had his ring and pinky fused to his palm, that didn’t stop his middle and index from doing just fine without them.

I do understand what you’re saying, but I struggle with dropping the idea of independence, because I see it right before my eyes that I can move each finger by itself, no matter what is going on under the hood. It’s essentially an emergent property. All the stuff thats in action and connected under our skin creating a new individual movement on the surface.

And the vulcan salute was to show it can be trained. I think you took that out of context. We both agree it can be trained.

Individual movement within constraints determined by the position and movement of the other fingers is not independence.

Then you and I are one. Can I have some money? Be nice to your family  lol

lol

Interestingly, while Allan has expressed that viewpoint, there were things in his mechanical vocabularly that were specifically facilitated by the G to B tuning. For more information, this video by John Vullo is an incredible work

Yeah, he said he learned the g n b minor 3rd so much he struggled unlearning it. But still the concept remains, using your inner voice to talk using the instrument should be the goal of people like me and others who not only want to express themselves, but learn music faster and remember it better.

Patterns are disconnected from music understanding.

And thank you for the links i’ll have a look.

For me it’s most important to turn my inner voice onto the instrument, i’ve forgotten so many lick, intros, phrases etc in terms of how to play it, yet I can still humm it. So there’s a clear solution, get my inner voice working on the guitar. And forget patterns, positions and licks.

If you can play anything in your mind on the instrument with almost no stumbling, then i’ll believe you. otherwise you have hit a brick wall.

An instrument is the same as a machine, as far as we are concerned as musicians, it transfers one force to another. That force can either be patterns that you’ve memorized, or your inner voice that is faarr more musical and useful than remembering patterns.

Forgive me for not being able type out a long response that your efforts deserve, I struggle with that.

No problem.

But this is like saying we all are not independent individuals. Because we’re massively influenced by our environment and our connections in life. But in practice, we face the world as an individual, just like the fingers move independently.

No, it’s like saying we’re not independent if I handcuff us together while we sit on the same bus. Our equations of motions literally become coupled.

You can lock the other fingers solid, and be able to move a single finger by itself.

Not so solidly as you could lock the fingers if you don’t move the single finger.

Yes it’s limited, but from your argument the only time a finger will act independently is when it’s chopped off.

I would argue it can’t act independently at all. Once you chop it off, the finger doesn’t act.

And the fingers literally have their own muscle associated with them.

Dude, I wrote about this in the last comment. They really don’t in any meaningful way. That’s the entire point. You are fundamentally minsundertanding the anatomy of your hands

I can move my index finger with next to no movement from the rest, for all intent and purpose, that finger is moving independently.

No, not for all intents or purposes. You cannot flex the DIP joint of your index finger (or any other) independently, and that matters.

I do understand what you’re saying, but I struggle with dropping the idea of independence, because I see it right before my eyes that I can move each finger by itself, no matter what is going on under the hood.

I did tell you you would struggle to let go of your presuppositions. What’s going on under the hood is the only thing that matters. Everything else is an illusion.

You seem pretty strongly set on your ideas of how things are “supposed to be”. Just in responding to me, you have ideals about the nature of your anatomy/physiology and their implications. In responding to others, you’ve demonstrated your ideals about musical understanding, expression and improvisation.

You called for a greater understanding of fretting hand mechanics. I have spent a lot of time studying this topic, with an honest effort to achieve more than the surface level understanding. I have read textbooks and watched lectures on anatomy, physiology and motor learning. I have studied footage of great players, observed and tried to understand what they actually do, rather than what people say or think they do. I have designed specific vocabularly to allow me to test hypotheses. I have taught professional semi-professional players from across the world and helped them to achieve results. I have taken my own playing to levels I would have previously thought impossible for me.

I don’t mean to position myself as the final authority. I certainly don’t know everything and I don’t claim to, but I genuinely don’t know of anybody else who is better informed on this topic than I am. If there were, I’d be referring to them and recommending their material. Yet after everything I wrote above to try to express to you that it just ain’t the way you think it is, you resist. Despite my genuine effort to help you, you’re convinced you know better. Why should I continue?

From what you’ve written here and in other threads, it really seems to me that you don’t actually want to improve, you want to confirm your subconscious biases. I don’t mean to single you out on this, our biases are deeply ingrained within us and this affects us all to some degree.

To learn any skill, you need to establish a robust feedback loop. We need to be able to avoid false positives and false negatives. If we cannot accurately assess whether we experience success or failure, we cannot make any meaningful adjustments. If we cannot make an accurate value judgement of “better” & “worse,” we cannot improve.

Your subconsious biases inform your ability to establish that feedback loop and make accurate those value judgements. They inform a preconceived “ideal,” which you will pursue and compare to, whether that “ideal” reflects reality or not. Bad assumptions lead to bad ideals. They’re not just a bug in the system you can work around, they’re a virus that infects everything you do.

I’m trying to tell you, in as clear a language as I possibly can, that the usual notions of “finger independence” and “economy of motion” are bad assumptions, which build bad ideals and inform bad value judgements. At best, they’re naive heuristics that have some limited, short-term value to beginners. Lies to children, maybe. In any case, they’re just plain wrong and don’t hold up against rigorous argument or careful examination.