More on the curious case of Paul Gilbert.

I’ve mentioned that Paul’s preferred fretting posture has a pronounced tilt/cant which facilitates (3 4) combinations. However, because the MPC joint of the index finger is behind the fretboard and the proximal phalange of his index finger is in contact with the underside of the fretboard, the range of motion and mobility of the index finger is limited in this posture.

In this posture, Paul typically plays repeating patterns where the index finger is typically relocated to the first note of the next position on the same string, or to the first note of the next string in the same position. Paul’s fretting posture and combinations are excellent in this context.

By using (1 3 4) combinations for whole/whole and whole/half figures, the low note in each figure is always fretted with the 1st finger and the high note in each figure is always fretted with the 4th finger. Paul almost always shifts on either the low or high note of a three note figure, and by using (1 3 4) instead of (1 2 3) for whole/half, there is never an incompatibility between Paul’s shifting strategy and his finger combinations. Moreover, using (1 3 4) for whole/whole simplifies Paul’s fretting sequences and helps to minimise the feeling of position shifting.

By shifting position, Paul simplifies his picking sequences. Essentially, it allows for an even number of notes on a string using 3 note per string scale shapes.

I mention to my students regularly that great players have synergies betwee their picking mechanics, fretting mechanics, fretboard figures and line construction. Paul’s playing on Intense Rock is an excellent example of this.

Greg Howe also used a similar approach for his picking patterns in his Hot Rock Licks instructional tape

However, Paul also plays a lot of string skipping patterns. Some of these patterns can be played with minimal deviation from Paul’s preferred fretting posture, because the index finger moves along the direction it points. Here’s a clear example:

And another. Notice the hyperextension at the MCP of the index finger on the high E string.

This is getting towards the limits of what Paul can do with this posture. For figures that require greater mobility and range of motion with the index finger, Paul adopts a different fretting posture. The wrist flexes, the MCP joints of the fingers come forward and lower. Here’s an example:

And another

In more recent years, Paul has begun incorporating (1 2 4) for whole/whole patterns more frequently, particularly lower in the neck. See here:

Notice the flexed wrist and the hyperextension at the MCP joint of the first finger.

It’s worth mentioning that Paul has also progressively incorpated more legato into his playing and that his guitar setup preferences have changed, moving to heavier strings and higher action to accommodate playing slide.

Now, let’s watch some Holdsworth. Notice the clear preference for angled fretting posture, and how enters more parallel posture when greater mobility is required with the index finger than MCP hyper extension provides:

Angled posture is awesome, and (3 4) is totally valid in many applications. However, it’s not without limitations. Gilbert is a tall man with large hands. Holdsworth was also very tall and had large hands. Vai is also tall with even larger hands.

Players with smaller hands, greater (3 4) length discrepency or greater anatomical fusion will have some trouble applying Gilbert’s approach in some contexts. For many, avoiding (3 4) in some contexts will yield better results. Shawn Lane consciously avoided (3 4), and it almost never appears in his playing. I’ve written about his playing extensively.

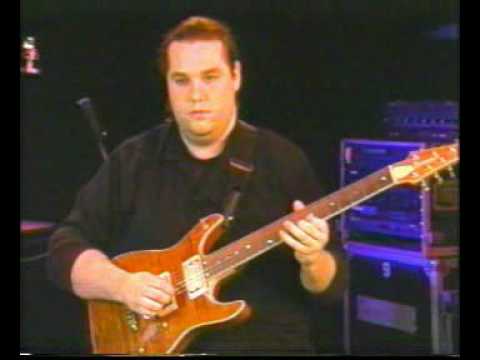

There are others – here’s Ritchie Kotzen.

Notice the preference for parallel posture and the clear discrepency in (3 4) lengths. Notice also that the slower demonstration uses (1 3 4) for whole/half (except on the low E string), and that the fast demonstration uses (1 2 3) for whole/half throughout.

If it wasn’t enough that he sings like Chris Cornell and writes great songs…