There is some pretty interesting discussion going on in this thread, and myself to have something to say about this.

A conclusion I have made after watching and applying CTC stuff, is that shapes aren’t the answer.

Let me elaborate :

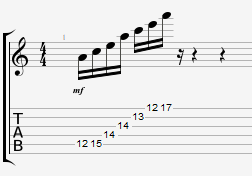

Let’s say I have learned an arpeggio shape like anyone else, that I know how intervals works, and that I can figure out in <2s the notes names looping over it :

If I want to go up the arpeggio by groups of 3, this shape is useless for that, it’s not faisable in string hoping. So you get another “shape” and play it with DWPS :

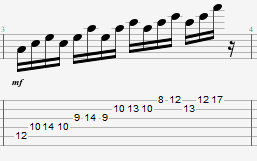

what about going down the triad in groups of 3 ? Well, another “shape” again, with UWPS :

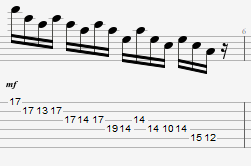

Do you see where I’m going ? Every simple concepts on piano/score sas groups of 3, 4, … often generate a new shape on guitar if you want to optimize string changes to play “fast”.

All that labyrinth of “fretboard mapping” needs to involve several instances of “map” to get around several concept ? No way, doesn’t seems like something feasible if you ask me, and if you watch close enough I bet you’ll see every guitar player going around one or two instances of their “map”, but not much more.

My point is, I don’t think “shapes”, “3 notes per strings modes”, etc, are the key to all of this.